Apr 21–May 18, 2022

Paige K. B.

Chapter 33

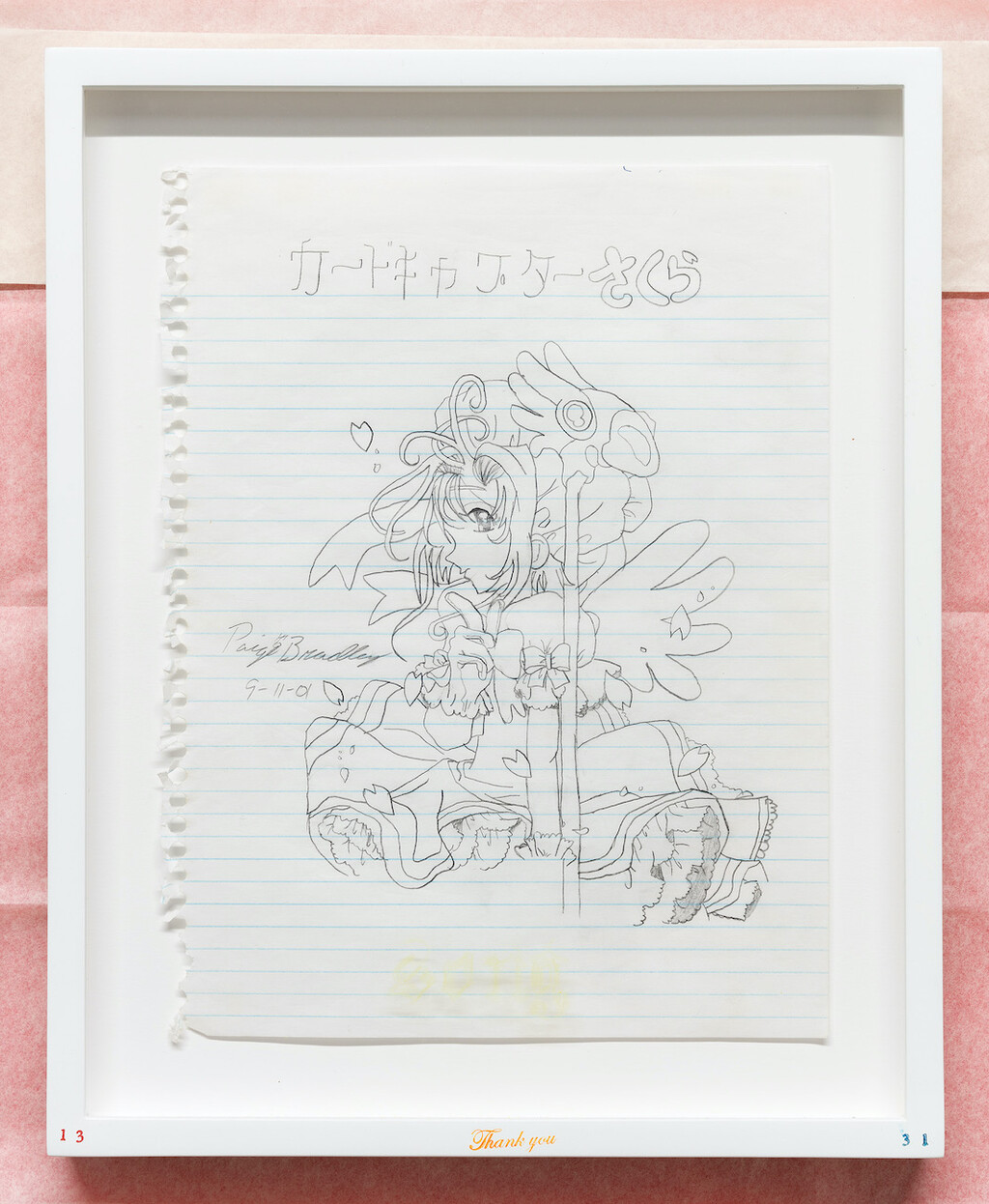

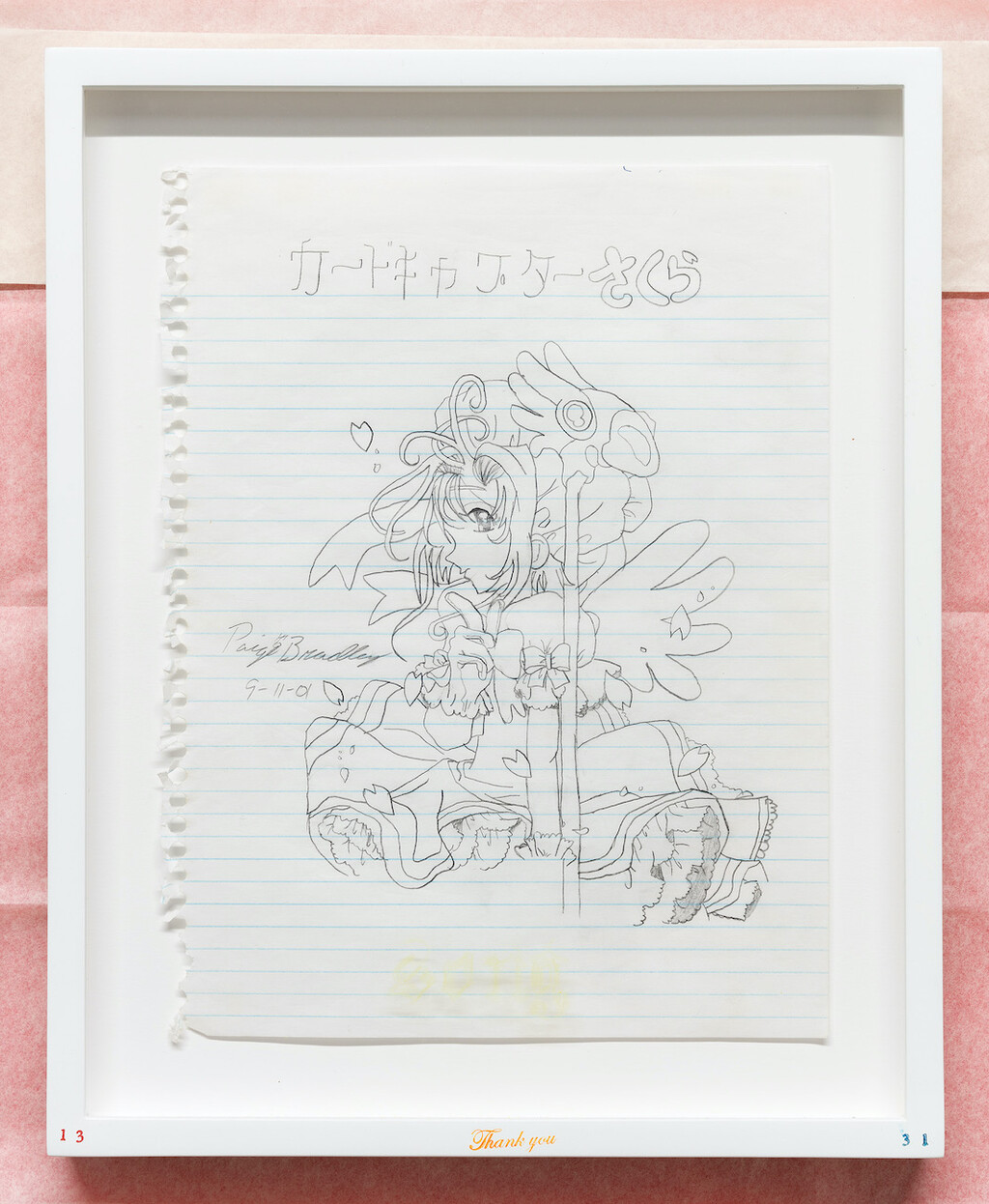

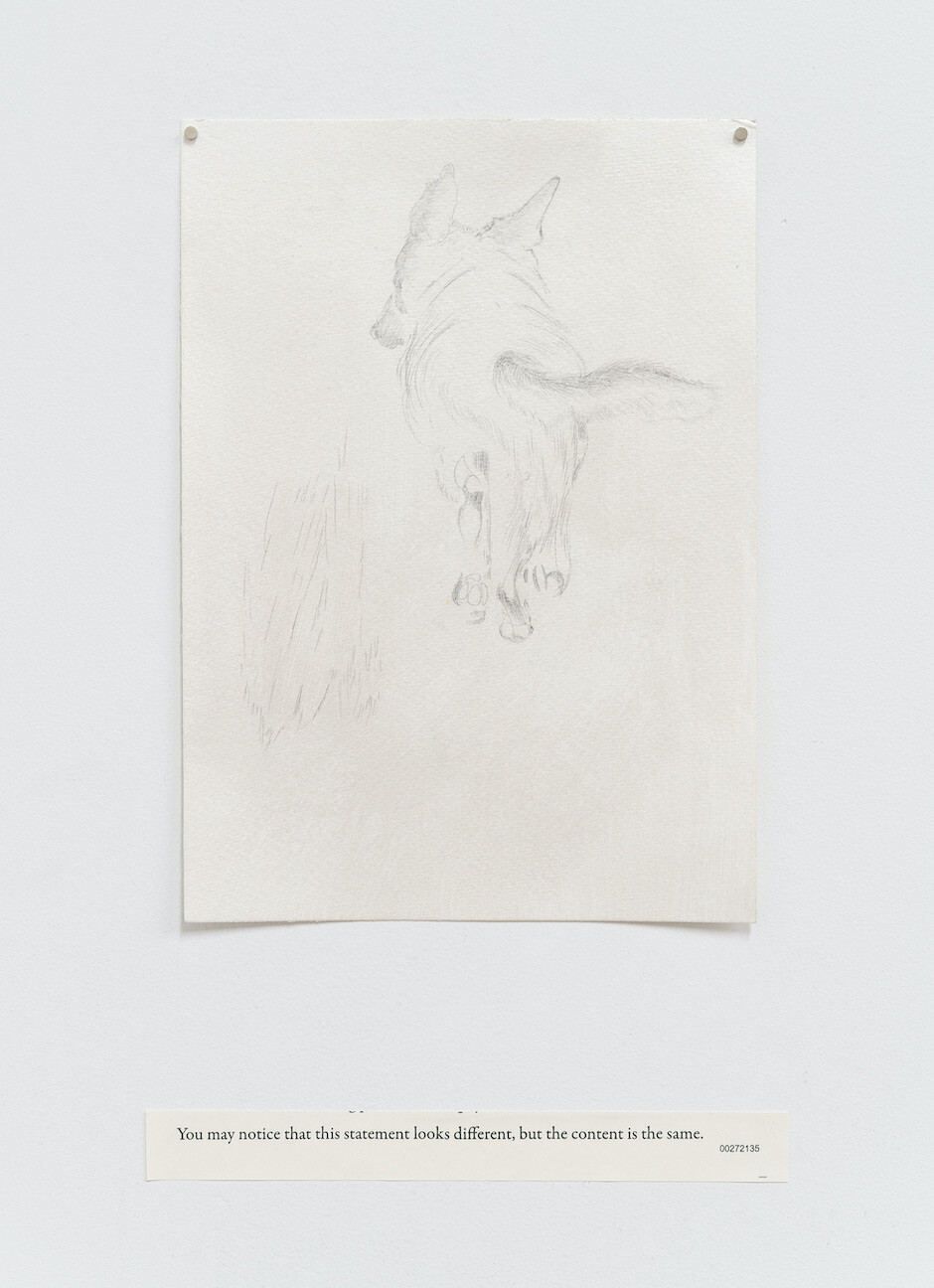

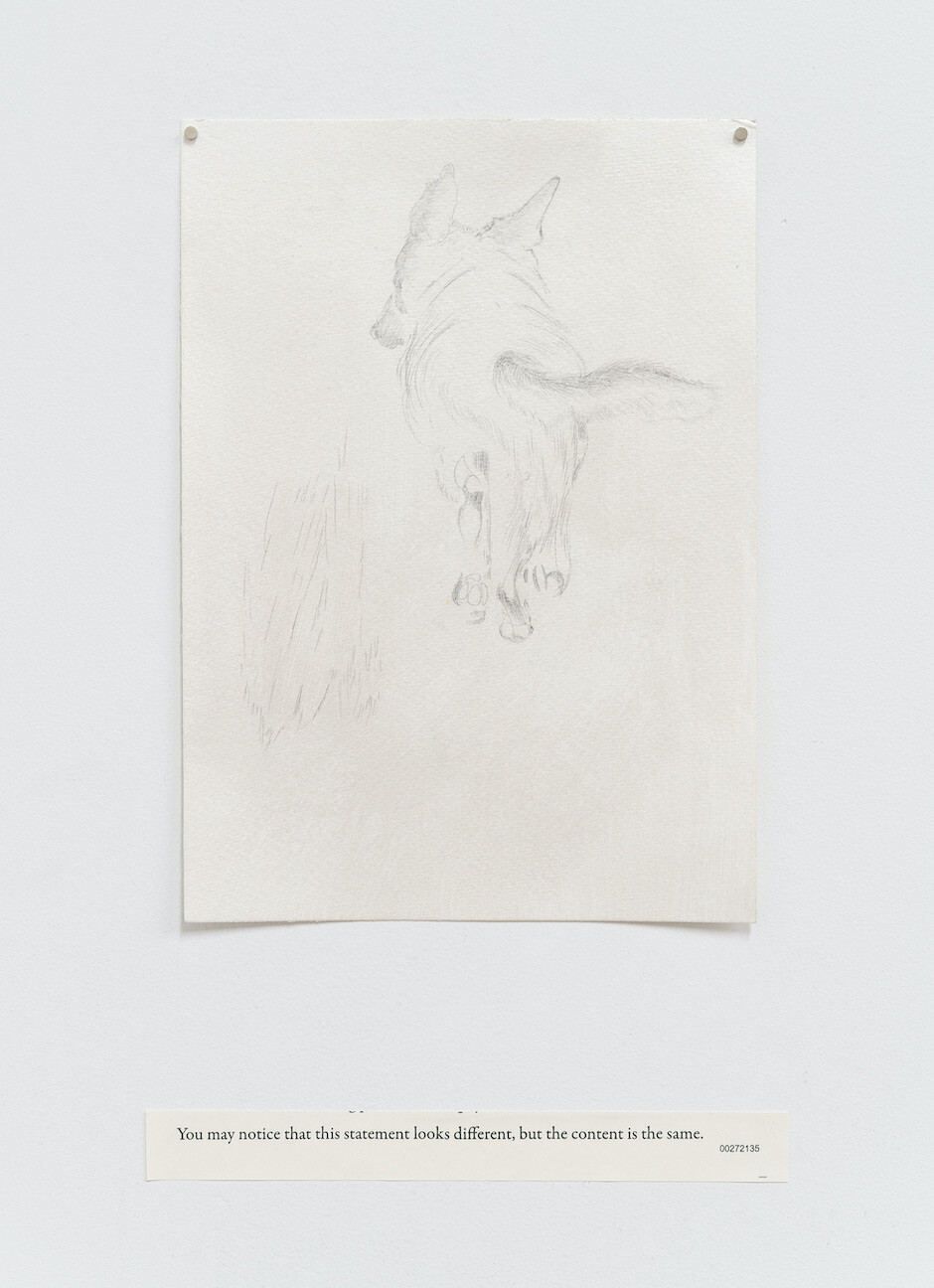

Let's, Say, Sing it Again, 2022, found drawing in pencil on paper, framed, ink, pencil, tissue paper, colored pencil, Pantone 19-1664 TCX True Red swatch card, and foil paper with Wedgwood ashtray and ashes, dimensions variable

Chapter 33 (installation view), 2022

The Unfunny Yellow Bird, feat. omens, 2021

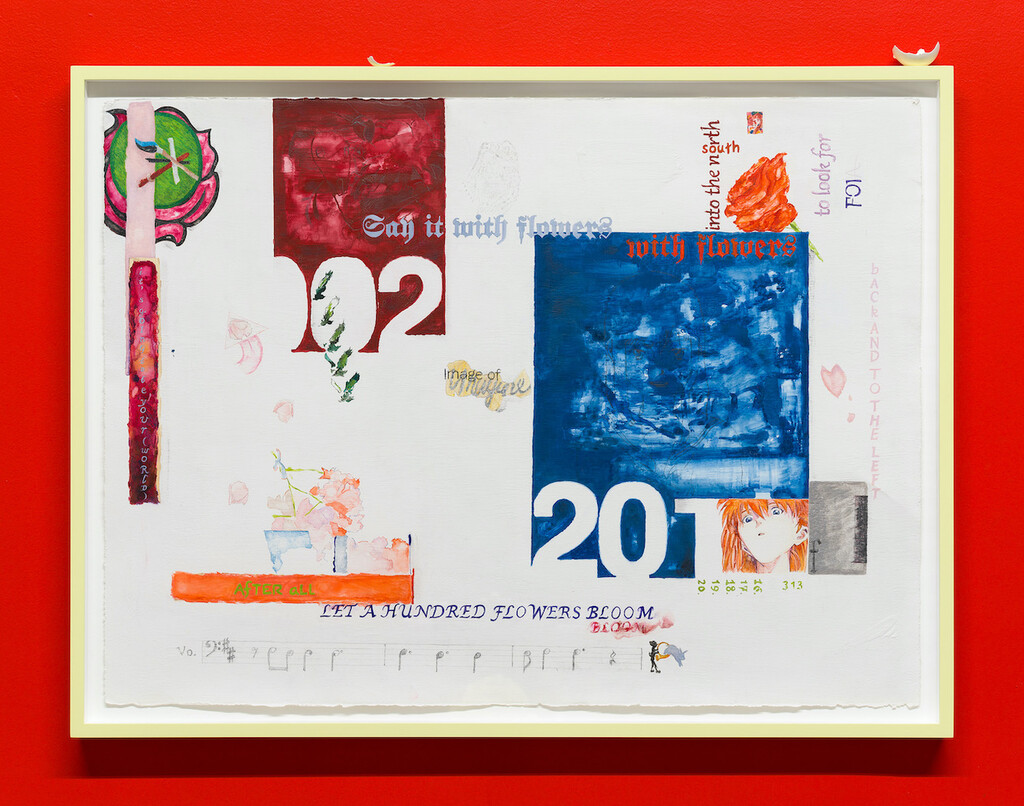

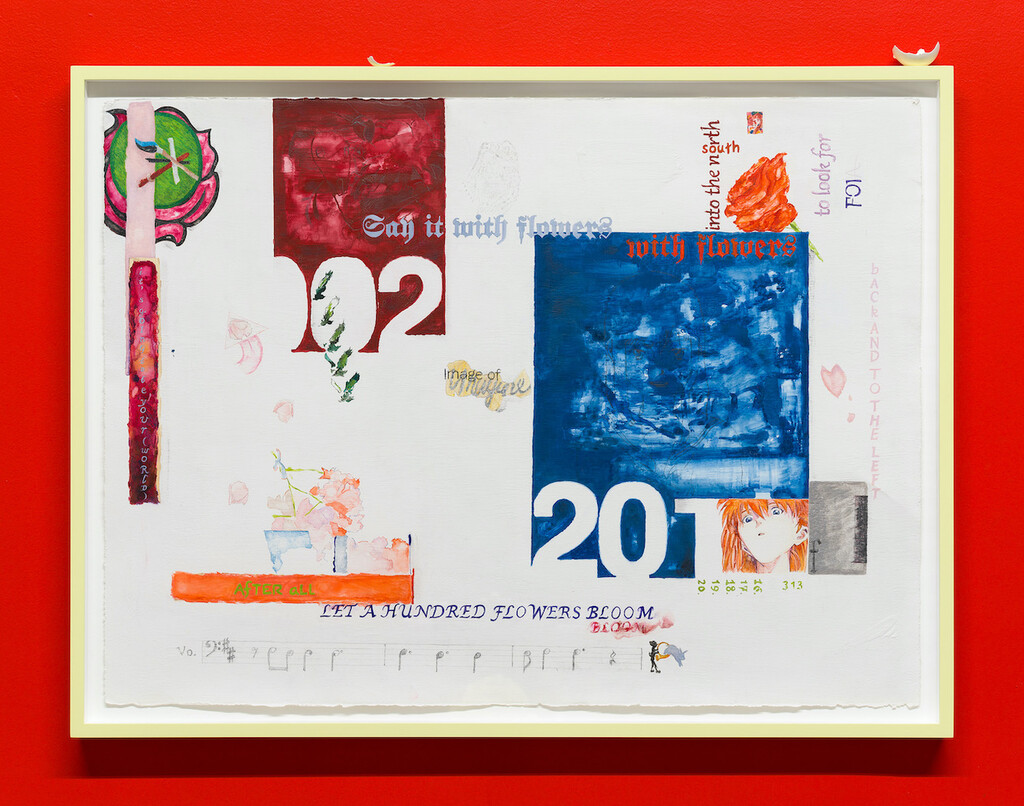

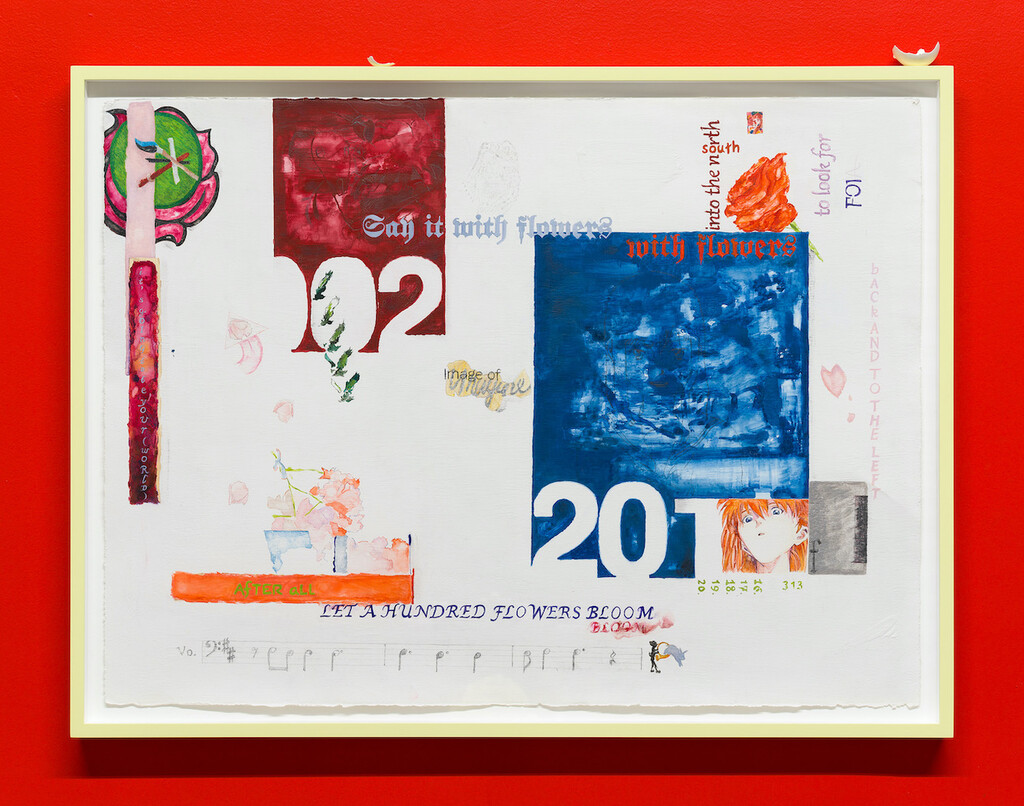

say it with flowers Like LET A HUNDRED FLOWERS BLOOM Like imagine!, 2020, gouache, egg tempera, watercolor, pencil, Urban Decay "ZERO" pigment, and acrylic on gessoed paper in maple frame painted Pantone 11-0618 TCX Wax Yellow, 24 x 32 inches

“Memory belongs to the imagination. Human memory is not like a computer that records things; it is part of the imaginative process, on the same terms as invention. In other words, inventing a character or recalling a memory is part of the same process.”

—Alain Robbe-Grillet, 1986

In the late nineteenth century, a woman burns her own house down, ostensibly to get what she wants. A chimney remains in the ruins, like a reminder of the promise of ash. But if I showed you a photograph of this scene, it would be at most halfway toward proof of the event. Further documentation would be necessary, unless you’re predisposed to take my word at face value.

A face confers values, and the one one chooses is a useful signal. But what is the content of an image, or a character, that cannot prove itself through surface alone? Further action required. It me? Multiply it, and the more you might realize how little you understand it—who left all these selves lying around? In the spring: shed my skin, leave it for someone else to sleep in. If you kick a dog, and it bites back, well, you know.

In her 2012 book Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, scholar Sianne Ngai sets out to examine the predominance of those “undeniably trivial” tropes in visual culture, each of which “revolves around a kind of inconsequentiality.” Cuteness, while “revolving around the desire for an ever more intimate, ever more sensuous relation to objects already regarded as familiar and unthreatening” might also evoke “a desire to belittle or diminish them further.” Cuteness, then, is adorably contemptible... because if we can hurt them? J’adore, we may as well.

A dead dog has no bite, but, instead, is plush in its abundance of memorable associations—this seems preferable to the potential dangers of an unruly animal still alive. Step on a snake, it snaps in reaction—this is natural. If I held out my hand, containing the skin off my face, as a gift, I wouldn’t be very lovable.

Characters, unlike people, are designed to be relatable. “Imagine how I feel!” Not unless you can tell a sympathetic story first. Say anything, but undergirded by the premise of character—a known and reproducible entity. Fictional as she may be, here she is.

A voice actress named Yuko Miyamura once said, regarding her playing one of the main characters of the anime franchise Neon Genesis Evangelion, that “Asuka was a young girl—a ‘part’ that taught me a lot. She wasn’t so much a part of my personality, as a separate entity inside of me—something close to a friend.”The happiest we ever see this Asuka—born in December, a fire sign, and perhaps a skosh over thirteen years old—is when she decides that the dead are protecting her, so there’s no way she can lose. She falls upon the world.

Asuka Langely is not a metaphor for childhood; she was made by an adult and can be remade any day of the week. She is plastic, she is variable, she is potentially in- finite, ergo I can use her however I like, just as a federal agency can choose anything it likes to base a warplane on. We share culture, we have designs on things. A crane for peace and a crane for war; opposites united in terrible consistency.

So, what happened to Chapter 32, anyway, or 30 or 19 or 27? Fell into the gutter—of the book? Light a match and take a look. Dead dog ate your homework? No, just lost in the post, I’d imagine. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chien.

Someone else

once said—

but we just don’t have the time to address that.

What we would like to say is something along the lines of “It’s your birthday, happy birthday darling—we love you very, very, very, very, very much.”What we should say is “I am afraid you are falling and we sold the house with the landing a very long time ago.”Write that on a piece of paper, toss it in the fire, and watch it, what’s the word, burn.

Projections of the Belgian artist Johan Grimonprez's 1997 film dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y—compiling archival media footage of various twentieth century plane hijackings with narrative voiceover excerpted from Don DeLillo’s novels White Noise (1985) and Mao II (1991)—will take place in the exhibition on Sunday, April 24; Thursday, May 5; and Saturday, May 14, all at 3PM EST.

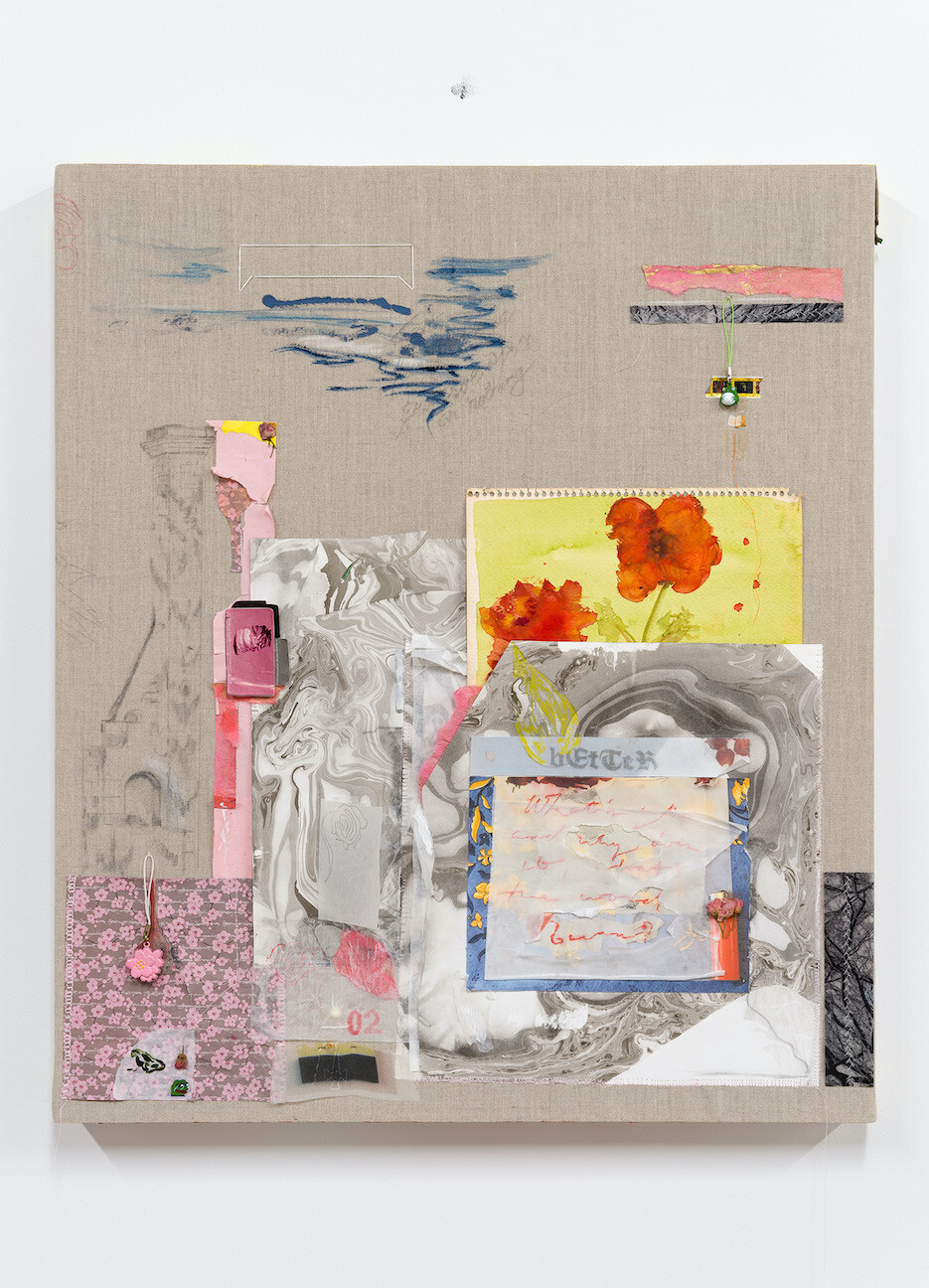

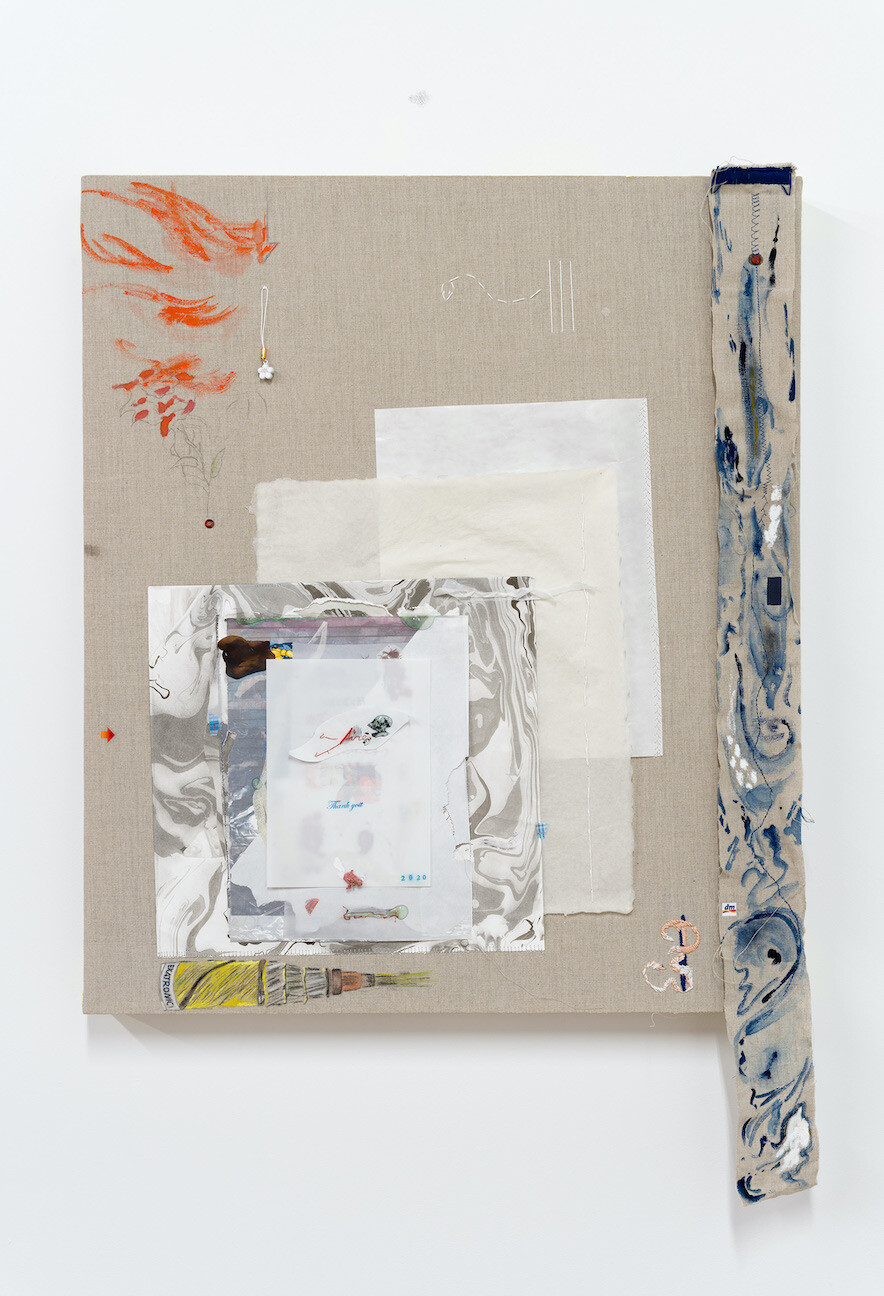

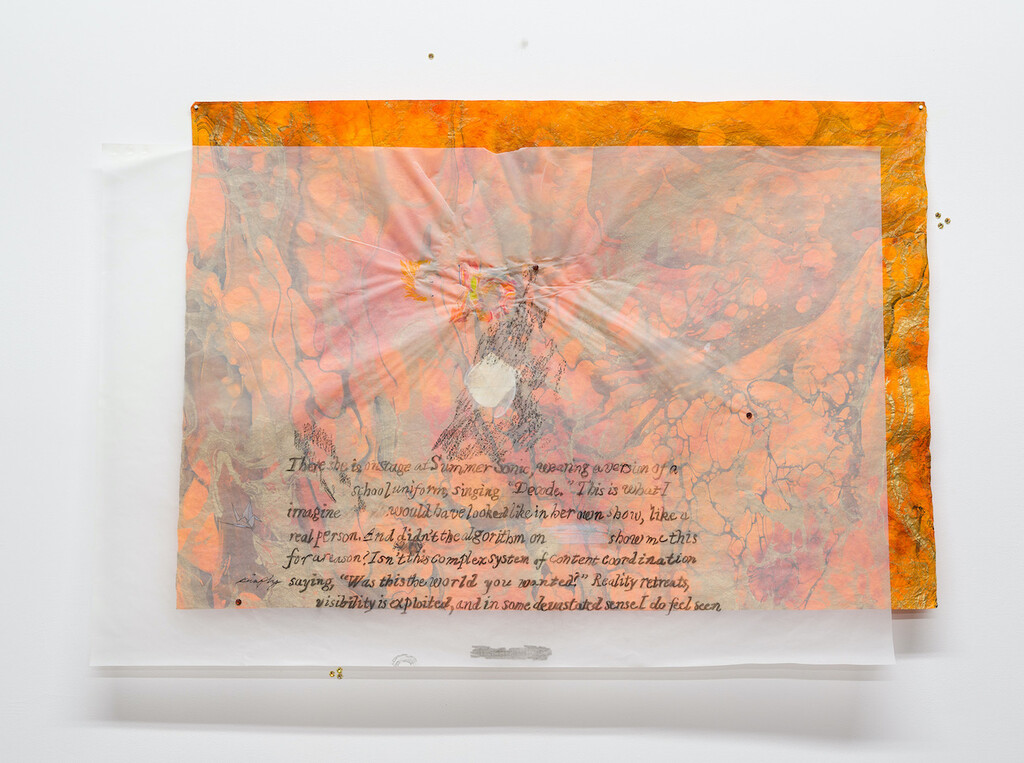

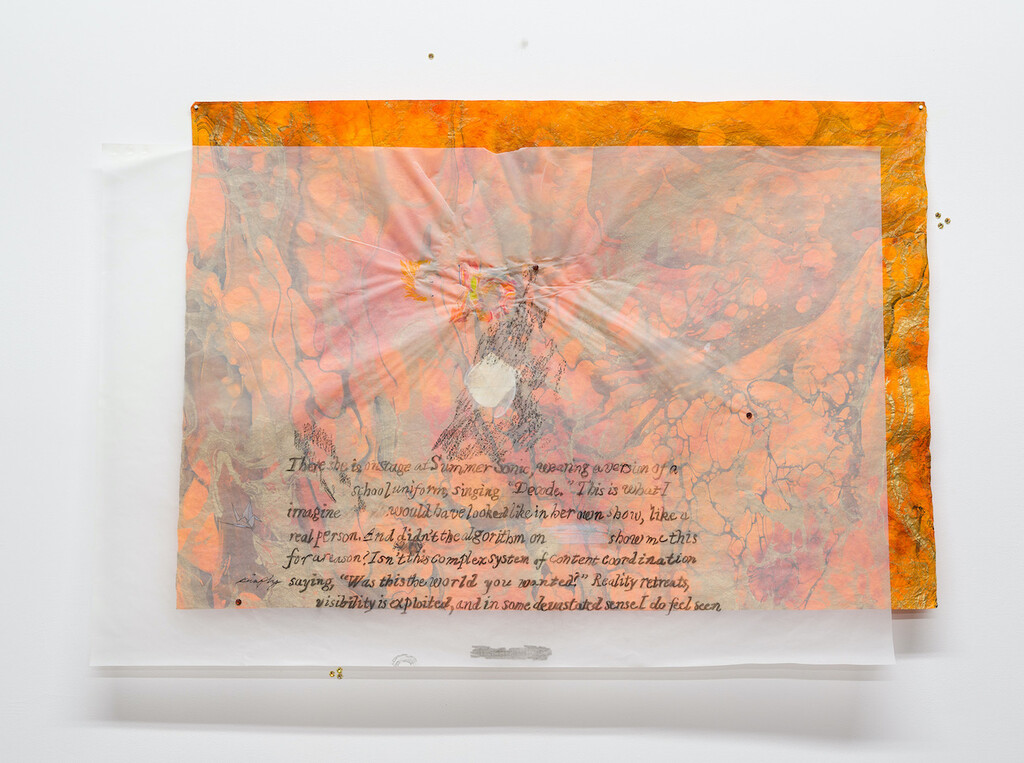

The Look Is Emo Gift-box for Spring Part 1, 2022, cotton thread embroidery, gouache, graphite, glassine, dried cherry blossom, New Models Codex Y2K20 sticker, mulberry paper, tracing paper, Swarovski crystal, digitally printed poly voile, hand marbled paper, tape, charm, found painting in watercolor on paper, tape, colored pencil, oil, and plastic on linen, 25 3/4 x 22 x 2 inches

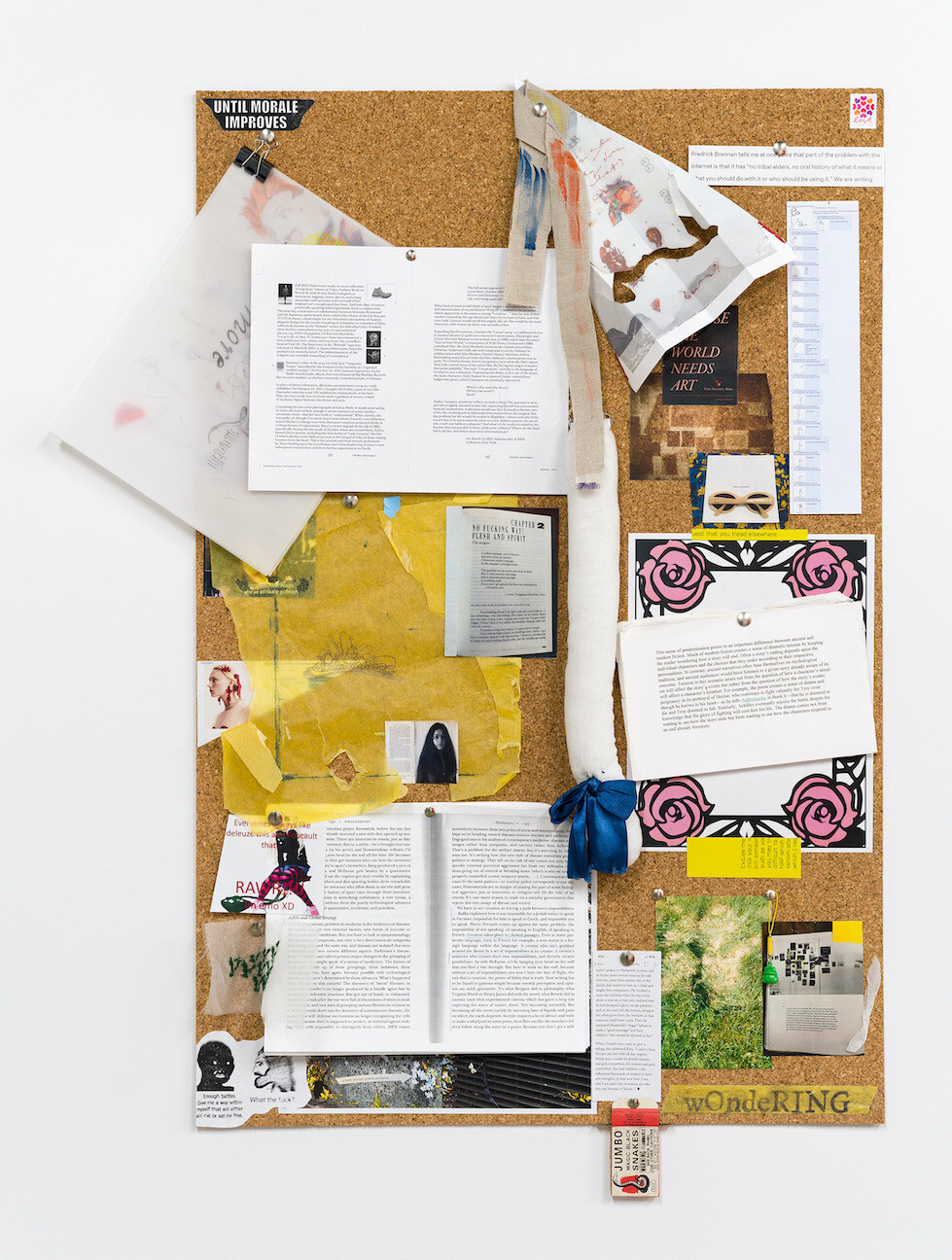

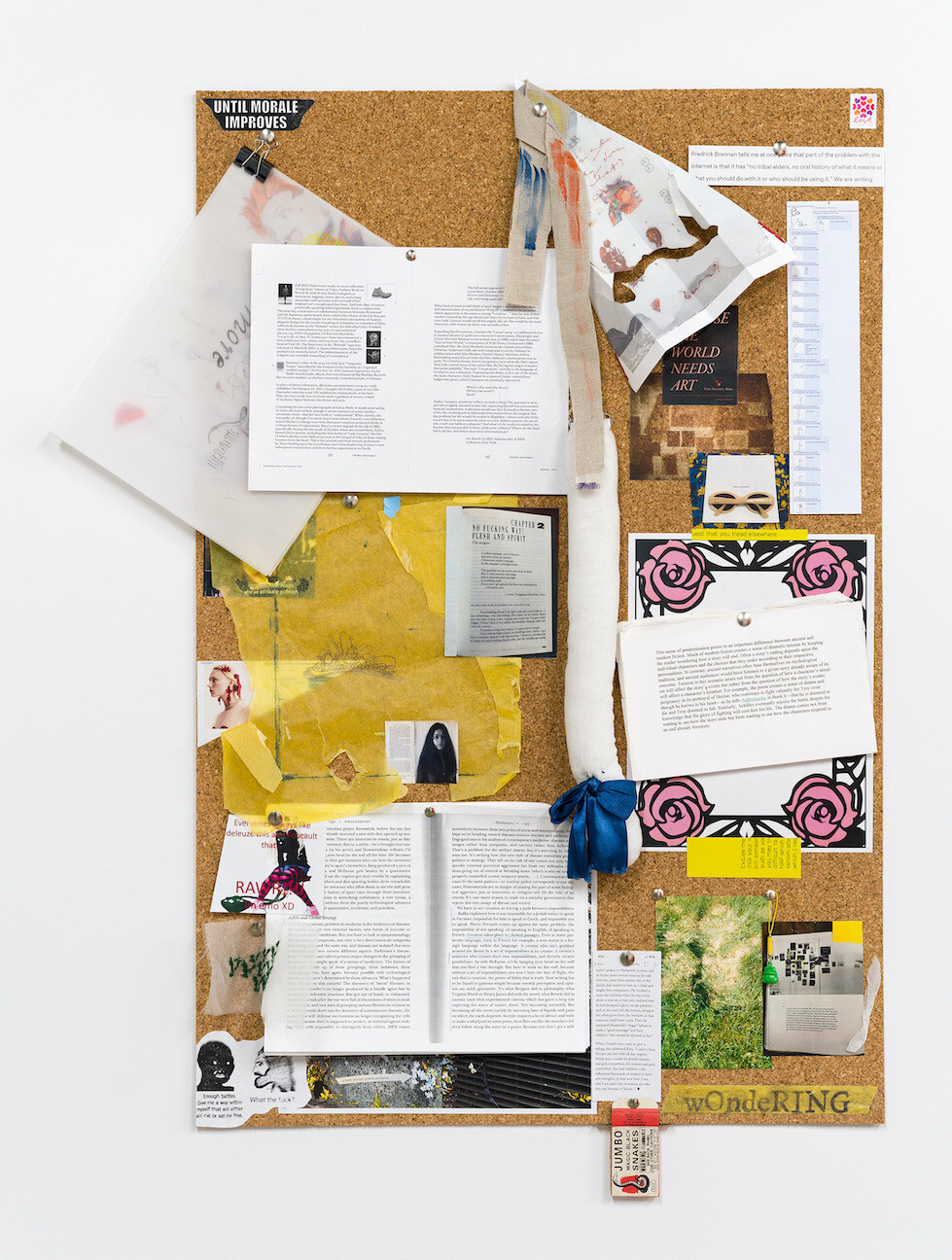

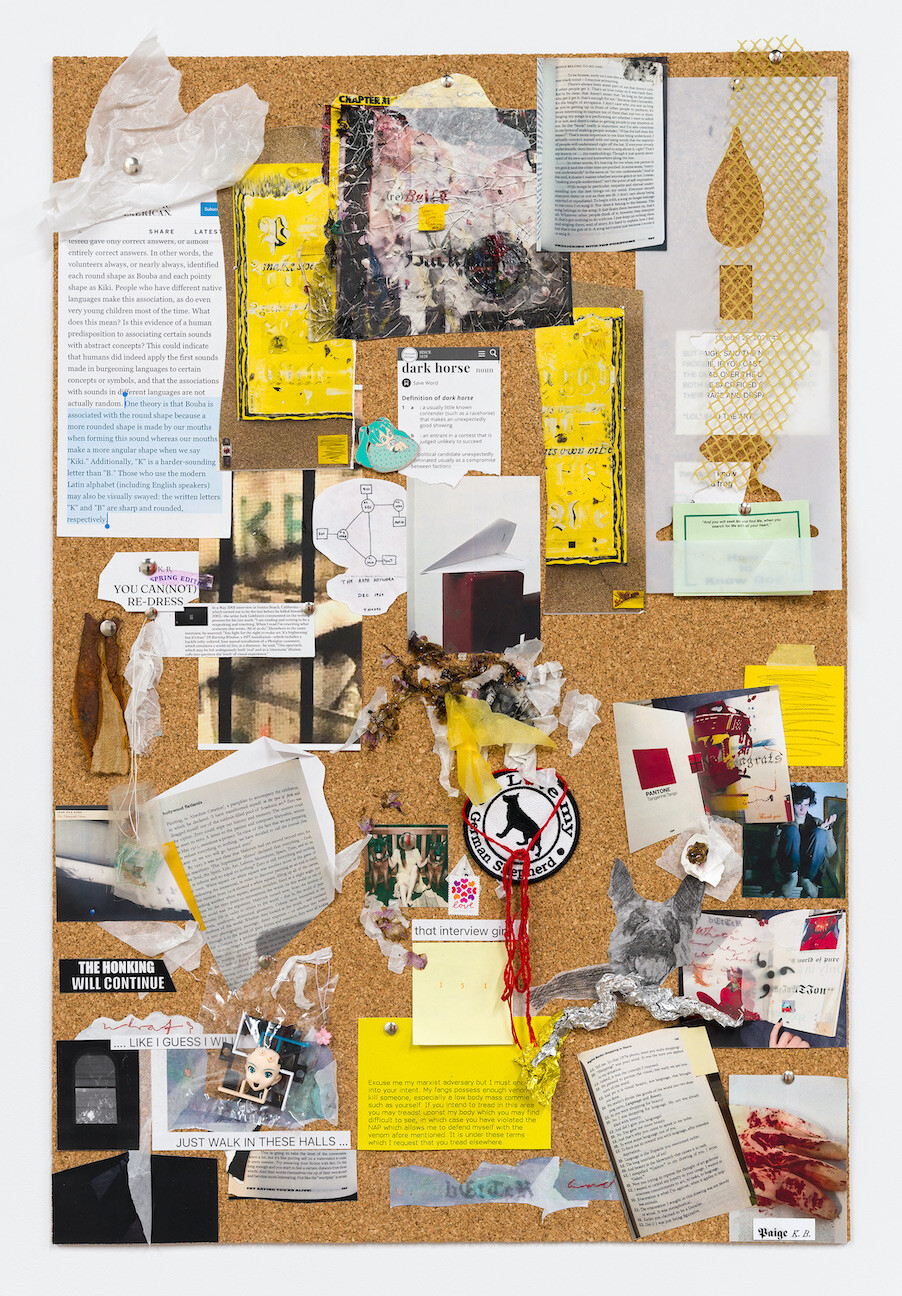

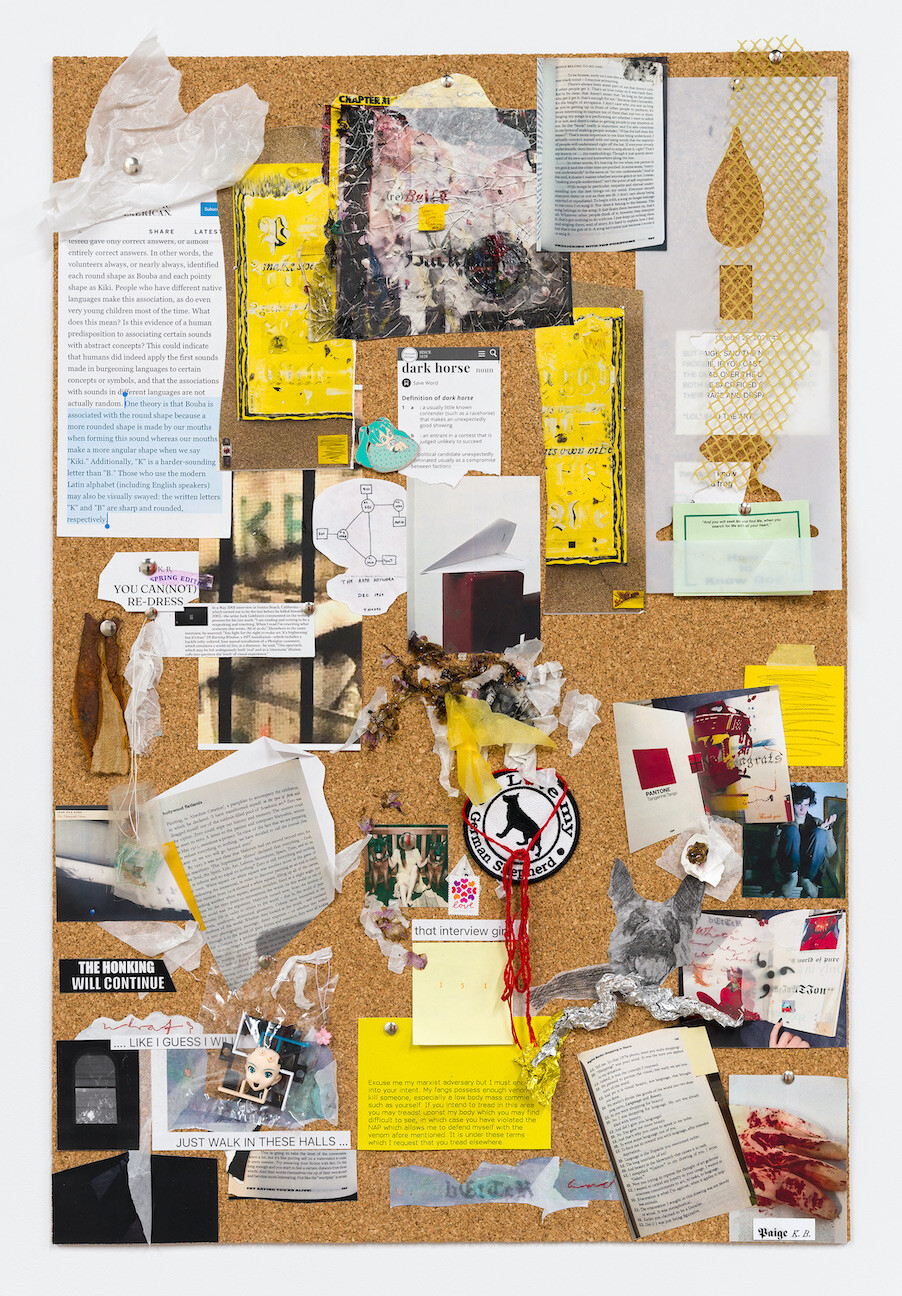

Process Retrospective Part 1, 2022, mixed media on cork, 36 x 24 inches

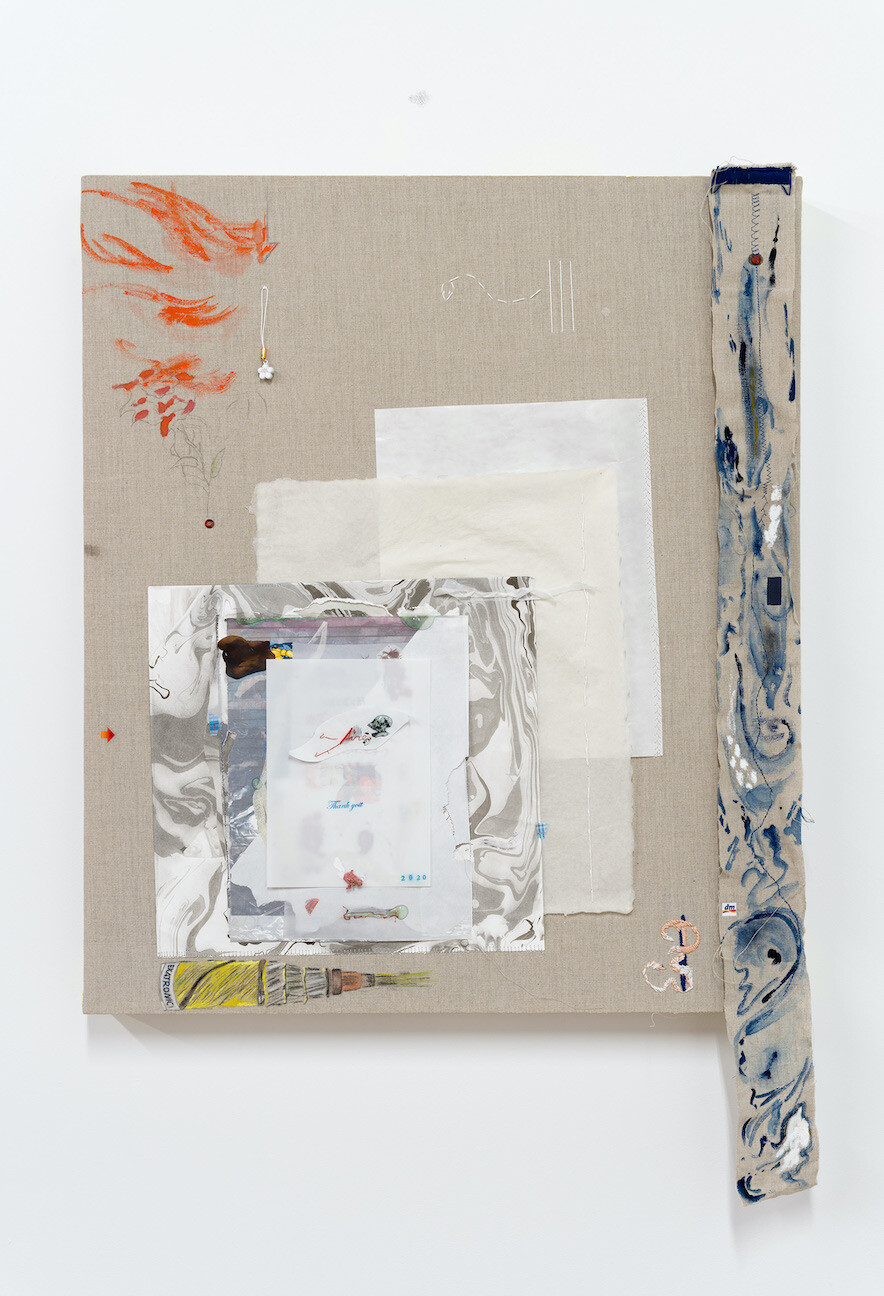

Congrats/Thank you, 2021, egg tempera, pencil, ink, and tape on mulberry paper, book-binding net, bookcloth, dried cherry blossom, oil pastel, water-soluble colored pencil, collage, and cotton embroidery on linen with ash-covered sugar cube and hand marbled paper, 24 1/2 x 35 3/4 inches

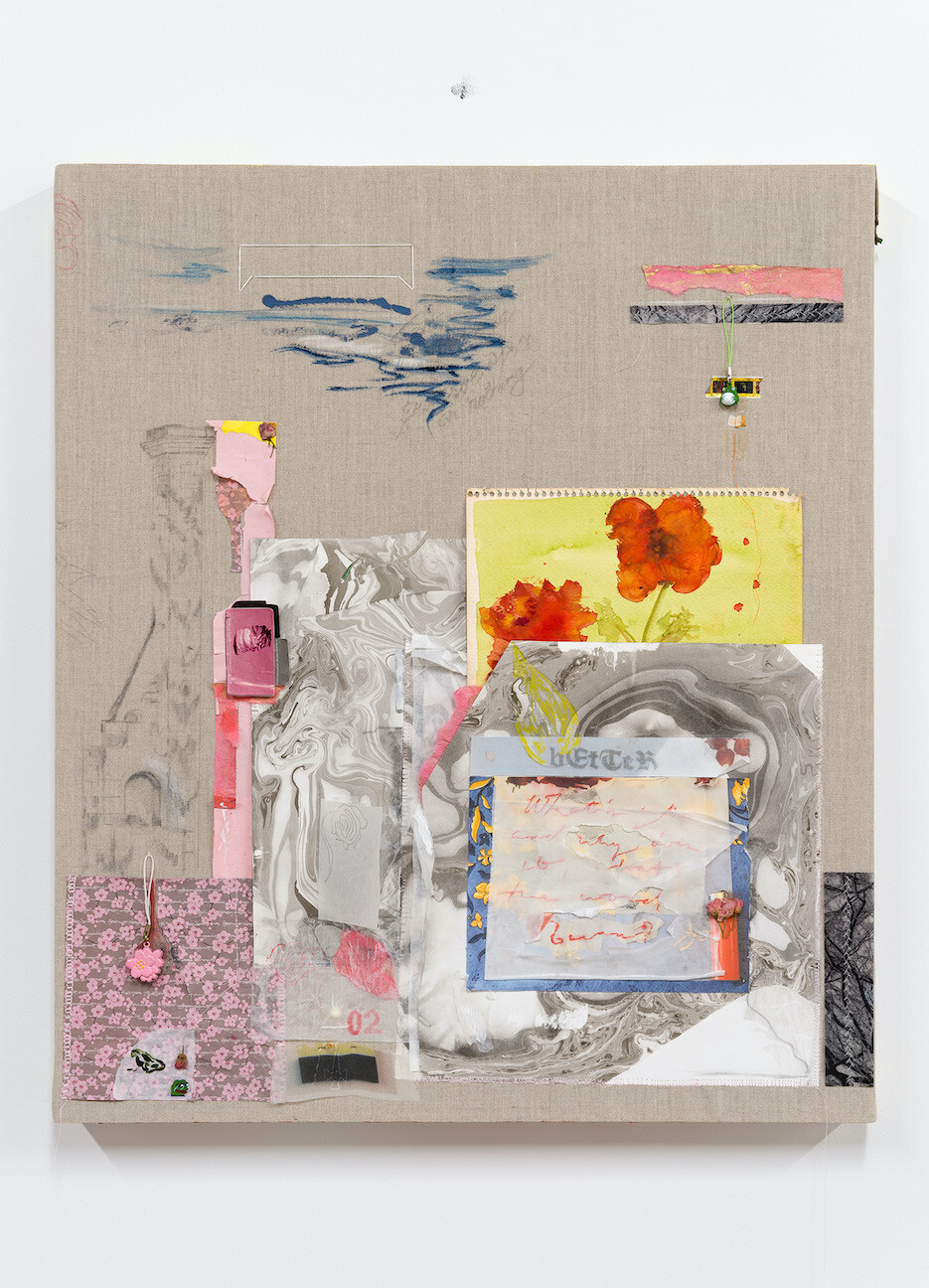

The Look is Emo Gift-box for Spring Part 2, 2022, gouache, cotton embroidery, charm, Swarovski crystal, acrylic, ink, glassine, handmade abaca paper, hand marbled paper, Yupo paper, New Models Codex Y2K20 stickers, tape, dried cherry blossom, oil pastel, egg tempera, water soluble colored pencil, and oil on linen, 31 1/2 x 22 2 inches

The Look Is Emo Gift-box for Spring Part 1, 2022, cotton thread embroidery, gouache, graphite, glassine, dried cherry blossom, New Models Codex Y2K20 sticker, mulberry paper, tracing paper, Swarovski crystal, digitally printed poly voile, hand marbled paper, tape, charm, found painting in watercolor on paper, tape, colored pencil, oil, and plastic on linen, 25 3/4 x 22 x 2 inches

Process Retrospective Part 1, 2022, mixed media on cork, 36 x 24 inches

Congrats/Thank you, 2021, egg tempera, pencil, ink, and tape on mulberry paper, book-binding net, bookcloth, dried cherry blossom, oil pastel, water-soluble colored pencil, collage, and cotton embroidery on linen with ash-covered sugar cube and hand marbled paper, 24 1/2 x 35 3/4 inches

The Look is Emo Gift-box for Spring Part 2, 2022, gouache, cotton embroidery, charm, Swarovski crystal, acrylic, ink, glassine, handmade abaca paper, hand marbled paper, Yupo paper, New Models Codex Y2K20 stickers, tape, dried cherry blossom, oil pastel, egg tempera, water soluble colored pencil, and oil on linen, 31 1/2 x 22 2 inches

The Unfunny Yellow Bird, feat. omens (detail), 2021, egg tempera, gouache, charcoal, and primer on wood; drypoint on Plexiglas, book snakes, eggshells, snakeskin, epoxy, dried cherry blossoms, wax, graphite, Kiiroitori San-X Original Plush, and charm, 45 x 13 x 13 inches

The Unfunny Yellow Bird, feat. omens, 2021, egg tempera, gouache, charcoal, and primer on wood; drypoint on Plexiglas, book snakes, eggshells, snakeskin, epoxy, dried cherry blossoms, wax, graphite, Kiiroitori San-X Original Plush, and charm, 45 x 13 x 13 inches

say it with flowers Like LET A HUNDRED FLOWERS BLOOM Like imagine!, 2020, gouache, egg tempera, watercolor, pencil, Urban Decay "ZERO" pigment, and acrylic on gessoed paper in maple frame painted Pantone 11-0618 TCX Wax Yellow, 24 x 32 inches

Let's, Say, Sing it Again, 2022, found drawing in pencil on paper, framed, ink, pencil, tissue paper, colored pencil, Pantone 19-1664 TCX True Red swatch card, and foil paper with Wedgwood ashtray and ashes, dimensions variable

Let's, Say, Sing it Again (detail), 2022, found drawing in pencil on paper, framed, ink, pencil, tissue paper, colored pencil, Pantone 19-1664 TCX True Red swatch card, and foil paper with Wedgwood ashtray and ashes, dimensions variable

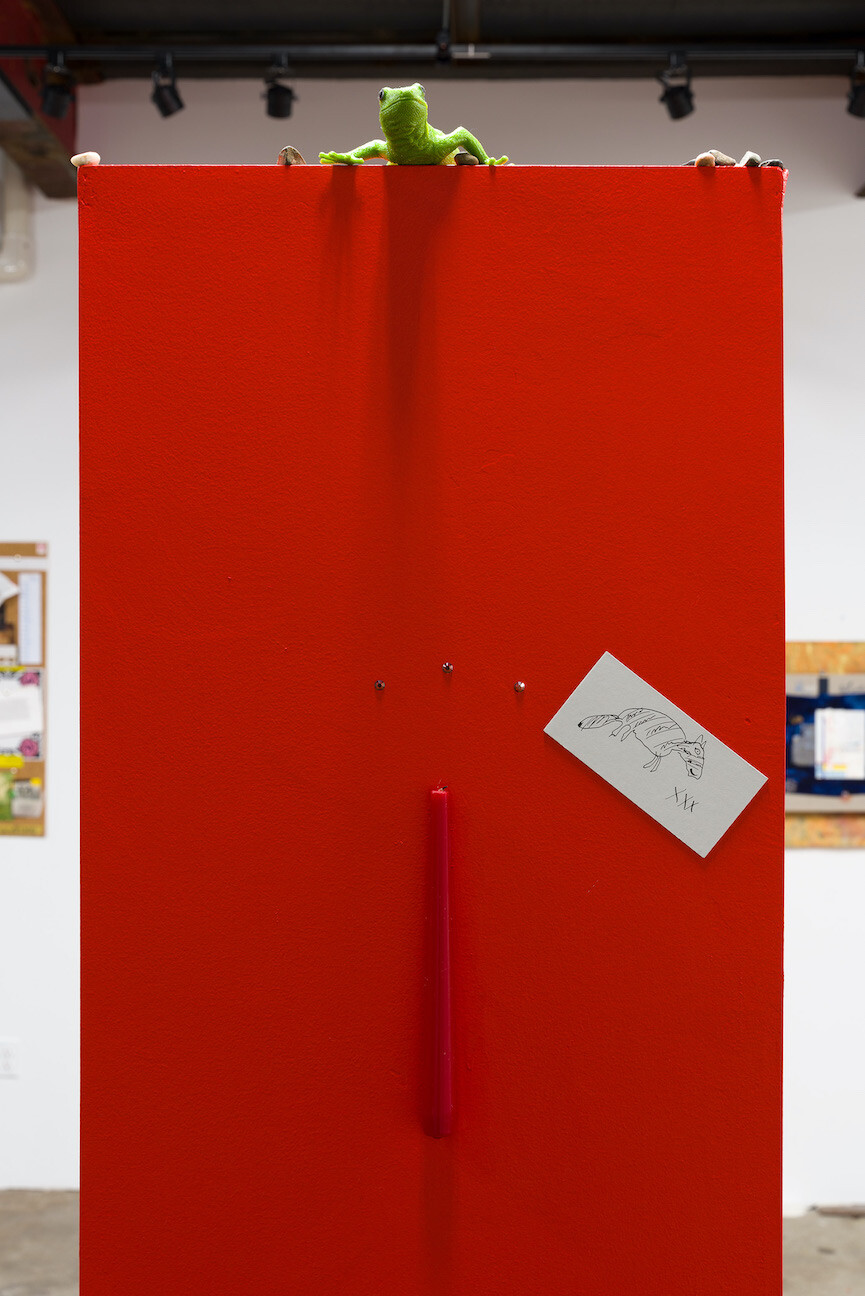

Don't Jump - Pool's Drained, Closed (after [>be me >reach third yellow light...]), 2022, rubber gecko, rocks, candle, found drawing, Swarovski crystals, drypoint on plastic Tupperware, coral, ash, dimensions variable

The Unfunny Yellow Bird, feat. omens (detail), 2021, egg tempera, gouache, charcoal, and primer on wood; drypoint on Plexiglas, book snakes, eggshells, snakeskin, epoxy, dried cherry blossoms, wax, graphite, Kiiroitori San-X Original Plush, and charm, 45 x 13 x 13 inches

The Unfunny Yellow Bird, feat. omens, 2021, egg tempera, gouache, charcoal, and primer on wood; drypoint on Plexiglas, book snakes, eggshells, snakeskin, epoxy, dried cherry blossoms, wax, graphite, Kiiroitori San-X Original Plush, and charm, 45 x 13 x 13 inches

say it with flowers Like LET A HUNDRED FLOWERS BLOOM Like imagine!, 2020, gouache, egg tempera, watercolor, pencil, Urban Decay "ZERO" pigment, and acrylic on gessoed paper in maple frame painted Pantone 11-0618 TCX Wax Yellow, 24 x 32 inches

Let's, Say, Sing it Again, 2022, found drawing in pencil on paper, framed, ink, pencil, tissue paper, colored pencil, Pantone 19-1664 TCX True Red swatch card, and foil paper with Wedgwood ashtray and ashes, dimensions variable

Let's, Say, Sing it Again (detail), 2022, found drawing in pencil on paper, framed, ink, pencil, tissue paper, colored pencil, Pantone 19-1664 TCX True Red swatch card, and foil paper with Wedgwood ashtray and ashes, dimensions variable

Don't Jump - Pool's Drained, Closed (after [>be me >reach third yellow light...]), 2022, rubber gecko, rocks, candle, found drawing, Swarovski crystals, drypoint on plastic Tupperware, coral, ash, dimensions variable

Build Back Better blue, 2021, collage and acrylic on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

There she is... excerpted from, 2022, colored pencil, charcoal, dried rose petal, graphite, mounted on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

She works for DARPA..., 2021, collage, graphite, acrylic, and oil pastel on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

Nobody Puts Baby in a corner (like so!) But otherwise, I'm Lover, I'm ZERO, I Leap Through Time (detail), 2022, Build-A-Bear Online Exclusive Zero plush, tissue paper, found rocks, tea rosebuds, acrylic and graphite on paper, ink-jet print, dimensions variable

Nobody Puts Baby in a corner (like so!) But otherwise, I'm Lover, I'm ZERO, I Leap Through Time, 2022, Build-A-Bear Online Exclusive Zero plush, tissue paper, found rocks, tea rosebuds, acrylic and graphite on paper, ink-jet print, dimensions variable

Build Back Better blue, 2021, collage and acrylic on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

There she is... excerpted from, 2022, colored pencil, charcoal, dried rose petal, graphite, mounted on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

She works for DARPA..., 2021, collage, graphite, acrylic, and oil pastel on marbled paper with Swarovski crystals, dimensions variable

Nobody Puts Baby in a corner (like so!) But otherwise, I'm Lover, I'm ZERO, I Leap Through Time (detail), 2022, Build-A-Bear Online Exclusive Zero plush, tissue paper, found rocks, tea rosebuds, acrylic and graphite on paper, ink-jet print, dimensions variable

Nobody Puts Baby in a corner (like so!) But otherwise, I'm Lover, I'm ZERO, I Leap Through Time, 2022, Build-A-Bear Online Exclusive Zero plush, tissue paper, found rocks, tea rosebuds, acrylic and graphite on paper, ink-jet print, dimensions variable

Process Retrospective Part 2, 2022, mixed media on cork, 36 x 24 inches

Chapter 33 (installation view), 2022

"TWIN INFINITIVES" C.R.A.N.E. Edition, 2022, polyester machine embroidery, polyester hand embroidery, acrylic, New Models Codex Y2K20 sticker, and collage on linen, 11 x 22 inches

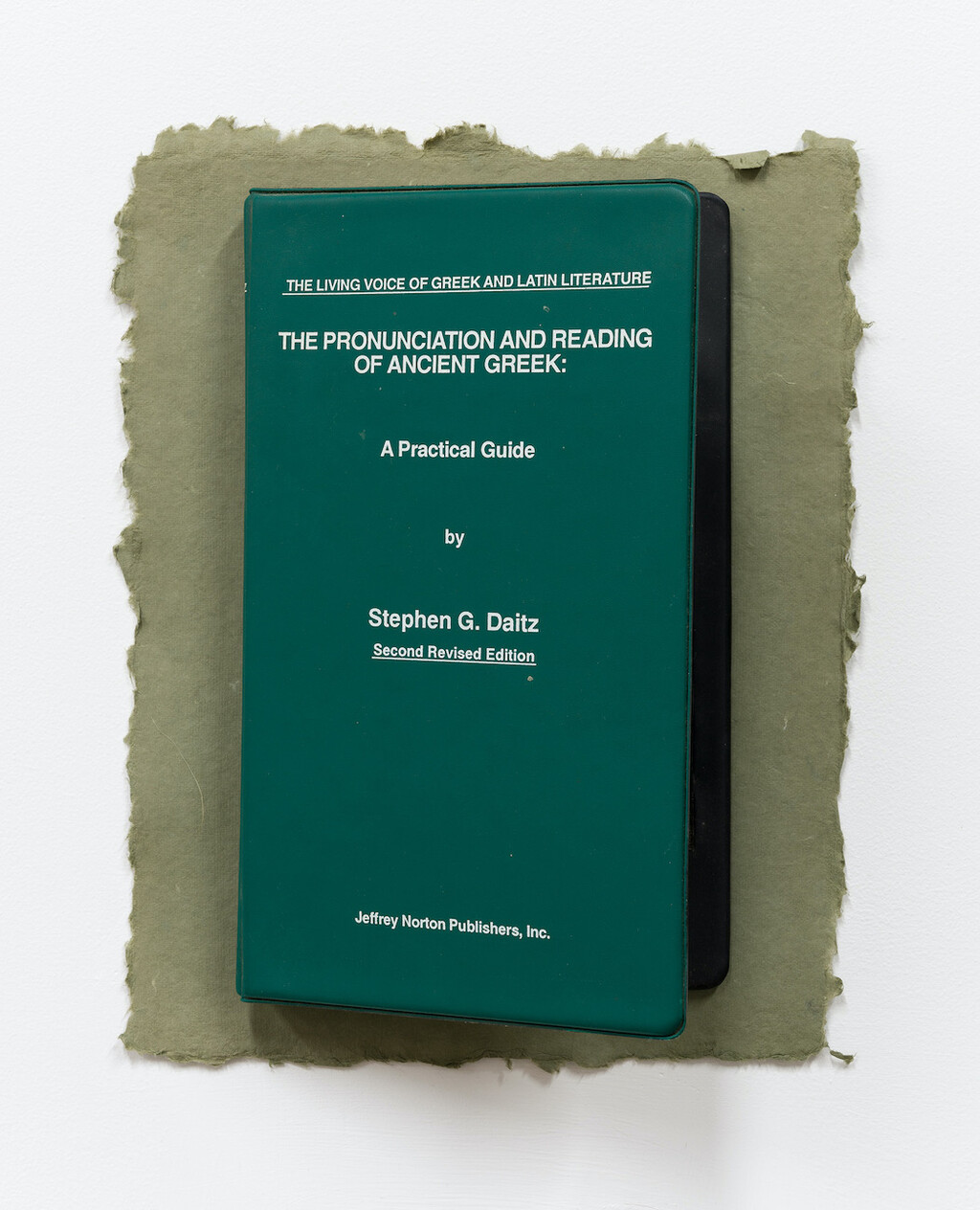

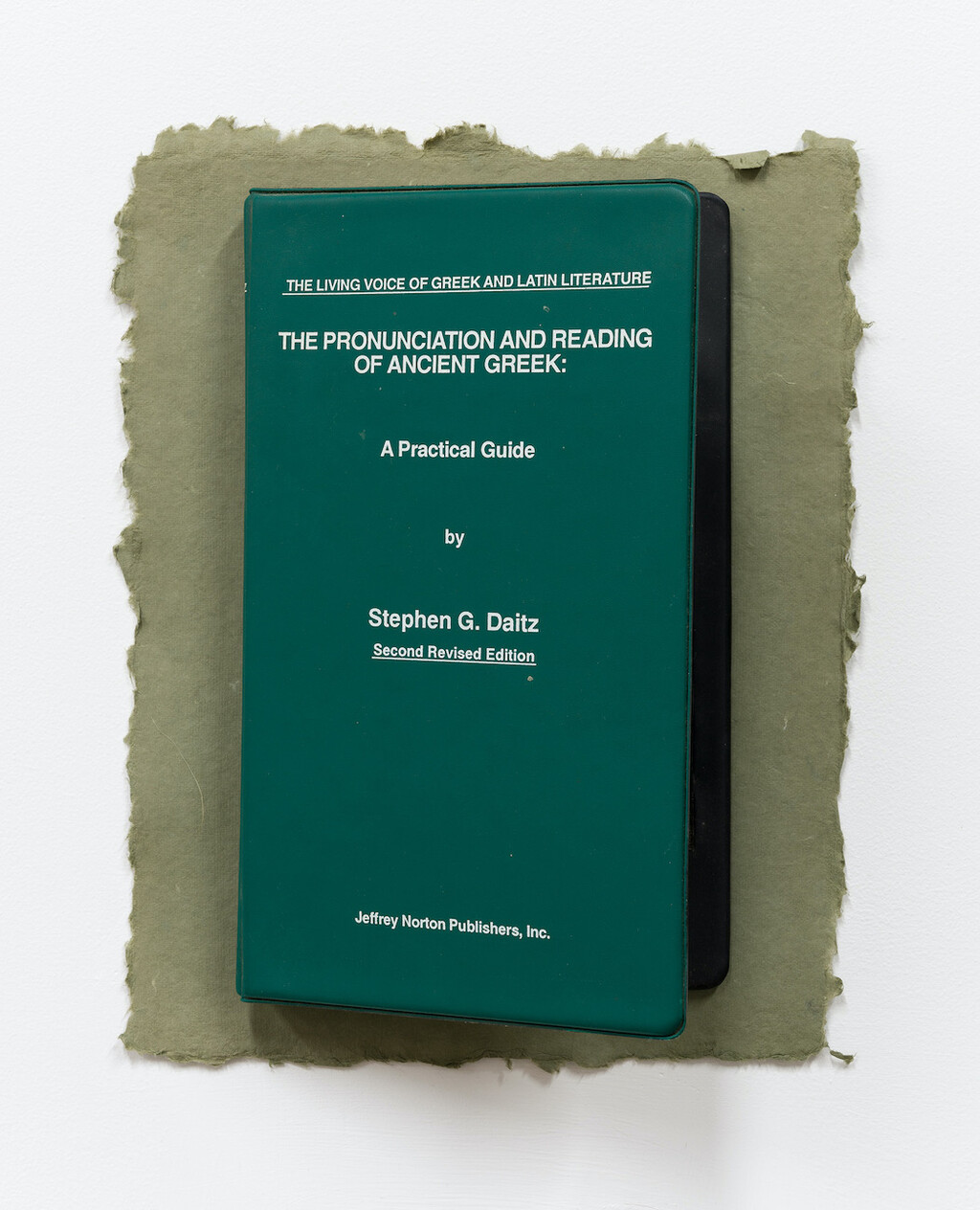

Would You Like to Hear the Tape?, 2022, stereo and cassette tape (2) folder mounted on Lokta paper, dimensions variable

Would You Like to Hear the Tape?, 2022, stereo and cassette tape (2) folder mounted on Lokta paper, dimensions variable

Process Retrospective Part 2, 2022, mixed media on cork, 36 x 24 inches

Chapter 33 (installation view), 2022

"TWIN INFINITIVES" C.R.A.N.E. Edition, 2022, polyester machine embroidery, polyester hand embroidery, acrylic, New Models Codex Y2K20 sticker, and collage on linen, 11 x 22 inches

Would You Like to Hear the Tape?, 2022, stereo and cassette tape (2) folder mounted on Lokta paper, dimensions variable

Would You Like to Hear the Tape?, 2022, stereo and cassette tape (2) folder mounted on Lokta paper, dimensions variable

For the closing of Chapter 33, KAJE invited filmmaker, artist, writer, and academic Heather Warren-Crow to read excerpts from her book Girlhood and the Plastic Image (2014, Dartmouth College Press) which argues that fundamental qualities of the digital image—namely, mutability, scalability, and shareability—are also associated with girlishness, with the power and vulnerability of girls as they are discursively understood. The author and the artist and writer Paige K. B. go on to discuss themes of Warren-Crow's research and key points of the book as they relate to the exhibition at KAJE.

BIO

Paige K. B. (b. 1988, Los Angeles) is an artist, writer, and editor who lives and works in New York. Recent exhibitions include a solo project at Lubov, a group exhibition at Theta, and an installation at Canal Street Research Association that developed into a collaboration with Shanzhai Lyric at MoMA PS1 for “Greater New York” (2021–22). Her writing has appeared across numerous publications for nearly a decade—including Frieze, Viscose, Spike, and Artforum—and her first book, a monographic essay on the art of Suellen Rocca, was published by Matthew Marks this year.