Oct 12–Nov 7, 2019

Elizabeth Orr

Assumed Room

Still undefined- the term "Mise en scène" is found!

One scene, which is the length of the video, manages to represent the entirety of the video.

Our interactions with buildings assume they are stable: Infrastructure engineered for our participation, their foundation's sound, constructed.

You are probably still, you are in a room or a subway car that shakes around you, walking very forward on concrete with a crooked neck. Your scene is assumed, while the building is slightly moving around you, undetected, not quite invisible, even in a reflection.

Cinema darkens the space, specifics of the room become unimportant, attributes forgotten. You sit, engaged as if standing around with others in a room. A gorgeous profile hidden: the well-lit front, and the backstage. Denial and illumination operating together. Asking- If we really felt like the spaces we lived in were slightly moving all the time, could we cope? If we really wanted to address the ecological disaster of single-use plastics- would we? These conditions for living surrounded by trash- all organized by both a methodical denial and illumination.

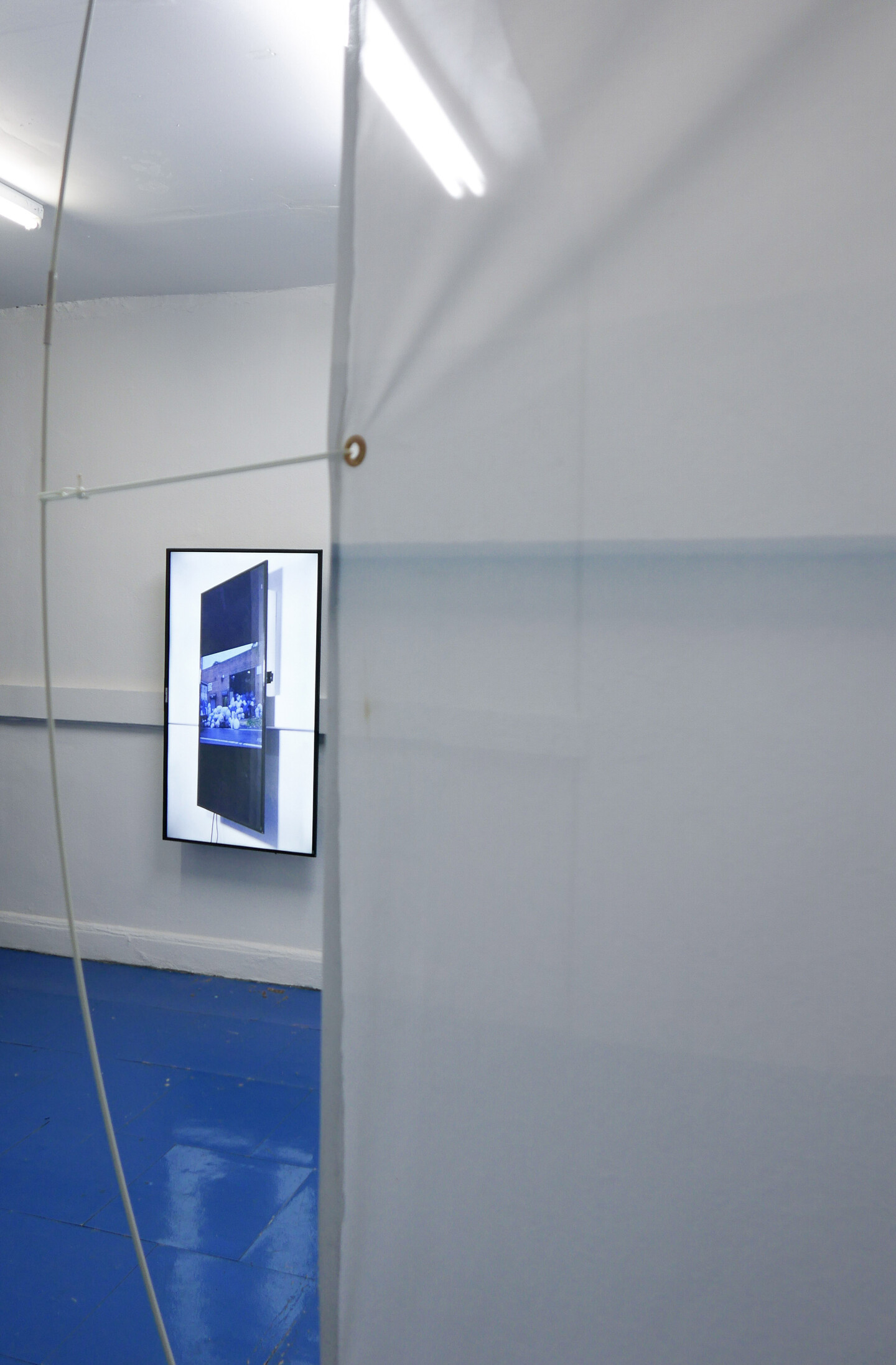

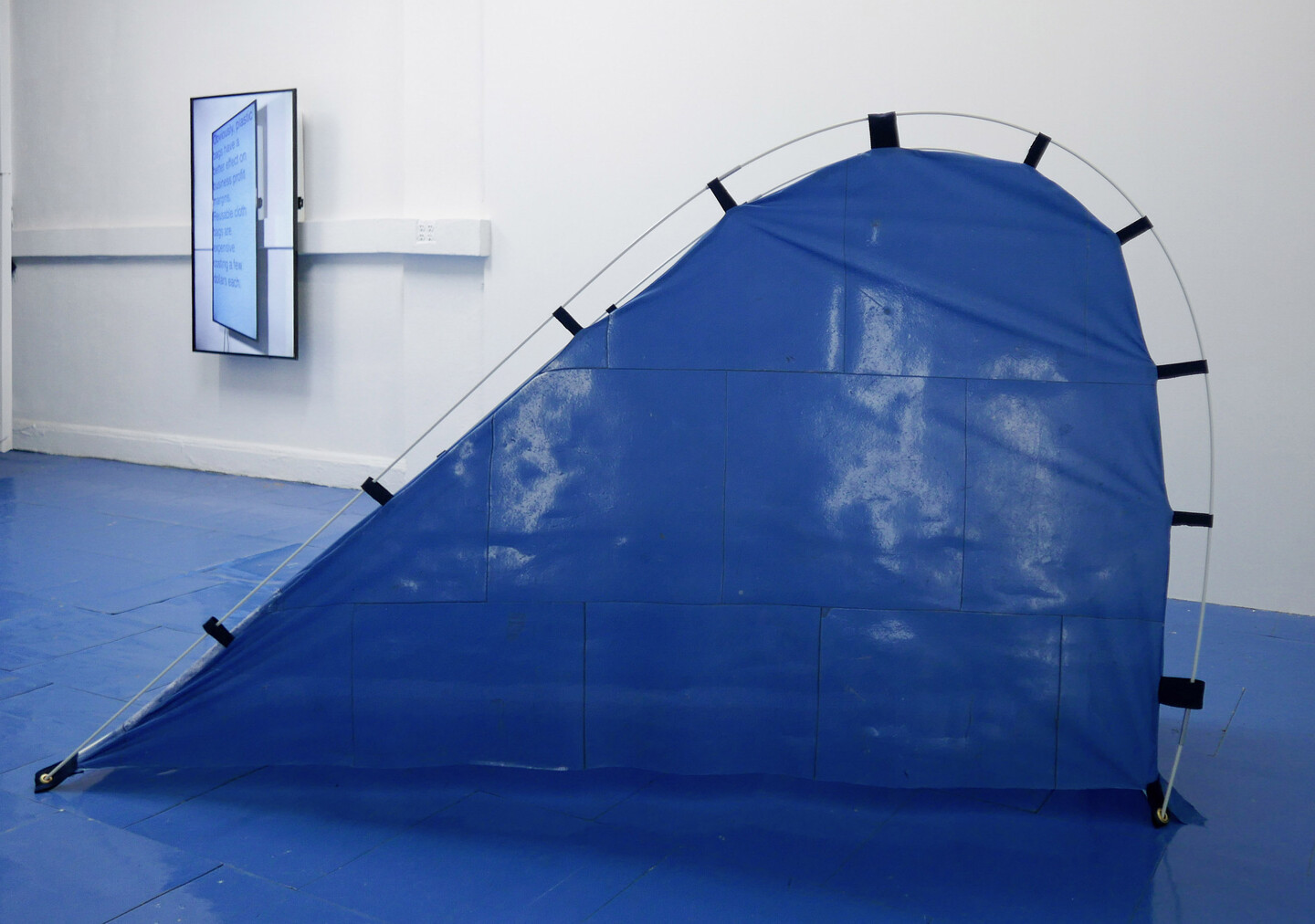

La Kaje is pleased to present Assumed Room, an architectural examination by artist Elizabeth Orr. Leading up to the exhibition's opening, Orr made a series of site visits to analyze the oblique features of our space, collect photographic measures, and determine a framework through which the gallery itself could be reconditioned/ upending our agreement to accept its stability.

Works Checklist :

'Drywall Wall,' 2019, Photo on Pongs Direct Tex,fiberglass poles, aluminium,12' x 13' diameter

'Tent,' 2019, Photo on Pongs Direct Tex,Polyester, fiberglass,74'' x 23'' x 54''

'Assumed Room #2,' 2019, Digital video on monitor, 4min.

'Assumed Room #1,' 2019, Digital video projection, 1min.

Elizabeth Orr (b. 1984 Los Angeles, CA) is a New York-based artist. Working with intuition, research, and humor, her practice involves an interrogation into philosophy and methodologies of thought and representation. She works through the idea that a methodology of thought can be materialized in art- literally how it is made, moved, and how formal qualities of art practice dictate a means to an end. Her work aims to celebrate art's potential to represent complicated subjectivity, positions, time, and movement. Her work has shown internationally, including The Stedelijk Museum, Bodega, Artists Space Books and Talks, Caro Sposo, Swiss Institute, Anthology Film Archive, Recess, ICA Philadelphia, MOCAïv, the Carpenter Center at Harvard University. She holds an MFA from Bard College.

Elizabeth Orr: A Gorgeous Profile

In his 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood,” Michael Fried argues that it is the duty—a spiritual vocation, even—of art to oppose theatre. Truly modern art is meant to present itself wholly and autonomously and require no audience for its completion. Minimalism, with its durationality and intersubjective call to the viewer, is, for Fried, a debased exemplar of theatricality. Cinema gets the rawest deal of all, I think, when Fried dismisses it as barely worthy of mention, since it is not adequately critical of the theatre/art divide:

Because cinema escapes theatre—automatically, as it were—it provides a welcome and absorbing refuge to sensibilities at war with theatre and theatricality. At the same time, the automatic, guaranteed character of the refuge—more accurately, the fact that what is provided is a refuge from theatre and not a triumph over it, absorption not conviction— means that the cinema, even at its most experimental, is not a modernist art.1

Though he does not fully contend with Fried’s assertion that cinema is complicit and escapist, Douglas Crimp famously takes apart “Art and Objecthood” in his theorization of Pictures, insisting that art should conversely be unafraid to intersect with the theatrical (though he does not deconstruct the latent homophobia of Fried’s use of that word, which Fried describes as a “faggot sensibility”2) and the durational and the contextual and even the melodramatic or autobiographical.

Crimp’s intervention became the standard by which we understand vanguard art to be liminal and performative, so it would be a cliché and limiting indeed to say that Elizabeth Orr’s show at La Kaje illustrates or becomes an example of the dispute surrounding Minimalism that I have outlined. We could say, for example, that Orr’s transformation of the gallery floor into a photographic sculpture, an impenetrable but loving refuge of architecture and image, could be seen as a combination of the photo-conceptualist discourse of the Pictures Generation with institutional critique, despite, or exactly because, those discourses are largely kept apart (I think, in part, because we associate women with the former and men with the latter and gays with neither). Since Crimp neglects to theorize the queerness that doubtless informed his reaction to Fried, we could say that Orr enacts a comical queering of the argument about what kind of affect and what kind of presence “good” art should maintain. It would be equally interesting to consider how Orr’s tactile presentation of a concentrated and out-of-place projected image affords the chance to resist absorption and instead understand film as a material, mappable, intimate, and critical entity, as is also the case in Orr’s 'MT RUSH' (2016).

These potential dissertations on Orr’s work can and should be written, but what I want to foreground here is everything that is not-always-critical (but not post-critical), because that is what the Fried-Crimp argument is really about. It is about to what degree criticism and history and aesthetics are affective and emotional phenomena, to what degree they all boil down to autobiography. Orr writes in the show’s press release: “A gorgeous profile hidden: the well-lit front, and the backstage. Denial and illumination operating together. Asking—If we really felt like the spaces we lived in were slightly moving all the time, could we cope?” A gorgeous profile, like Sherrie Levine’s silhouettes of famous men that would inspire Crimp to write his Pictures essays. A gorgeous profile, like the things that art critics write about artists in 'T: The New York Times Magazine' or 'Vogue'. A gorgeous profile, like a coin, or a not-so-gorgeous profile, like anti-Semitic propaganda. A gorgeous profile, like somebody’s face we have touched in a manner that is both sentimental and highly self-aware (Fried and Crimp are both in equal measure and in not-so-different ways).

That skin we have seen and touched becomes a monument (albeit one that is neither nostalgic nor resistant to deflation) in the form of Orr’s wall-as-screen, which lives before (or maybe “for,” in the relational sense despised by Fried and fetishized by Crimp) the projected image and not behind it. Its function is not to present or frame the image, therefore, but rather to exist lovingly in proximity to it, as we might with characters onscreen or in memes. We might imagine then who or what resides in Orr’s closed-off tent that seems contiguous with us, inasmuch as it is the floor we walk on, and abjectly and painfully distant, like a cancerous lump that is divided from our bodies by a line of hardened flesh or polluting plastic. Above all, we could wonder whose profile has been hidden, according to Orr, and whose floor, whose history we would like to transform into something that might potentially swaddle us or irk us so greatly that we create an academic or aesthetic rebuttal.

-

Gregory Battcock ed., Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 141.

-

I owe this point to Amelia Jones. See also Christa Noel Robbins, “The Sensibility of Michael Fried,” Criticism: Vol. 60, no. 4 (2018).