I’m here at the show, getting nervous about it

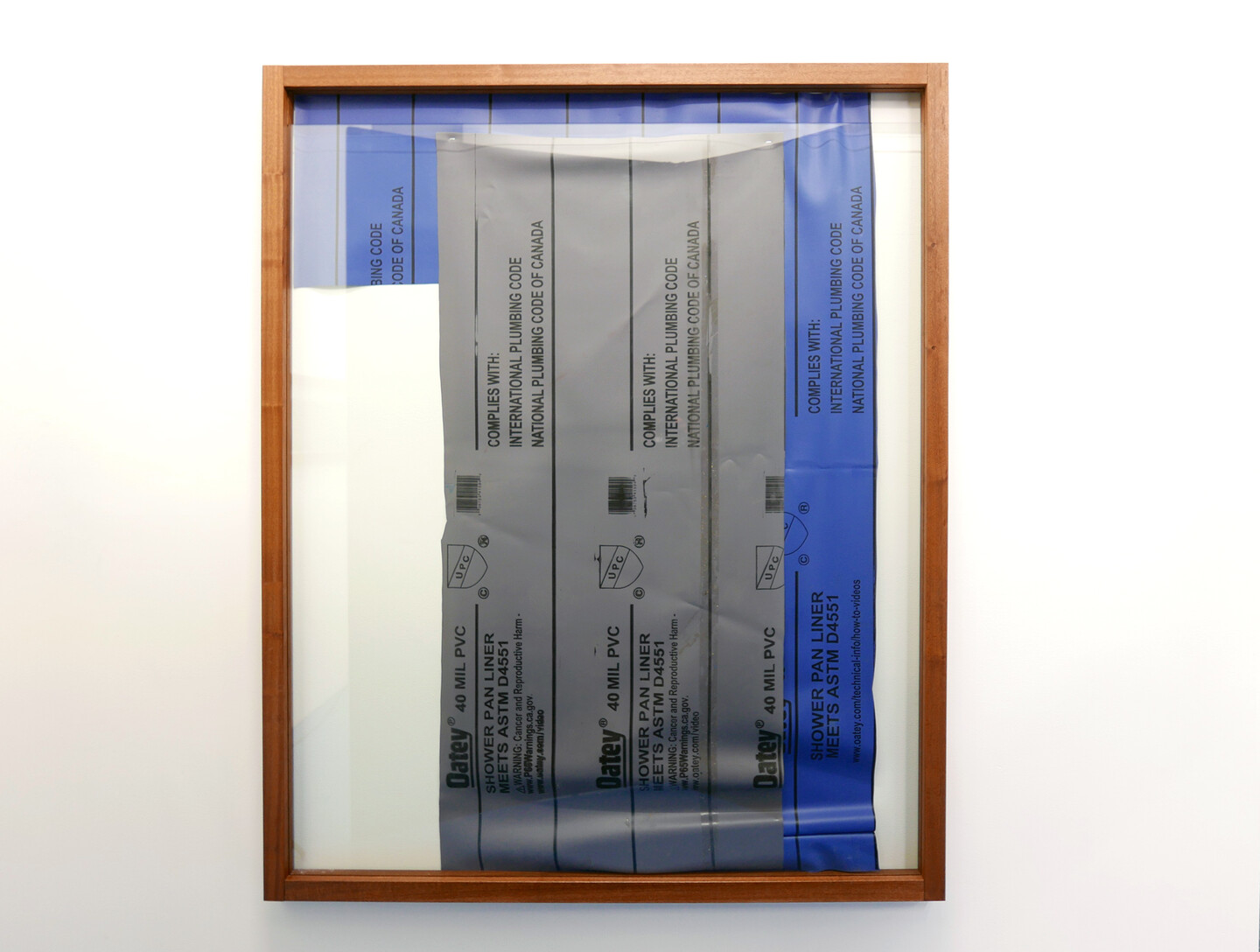

the show of Andy Meerow and Rose Marcus, two friends in conversation. The pieces are as follows: Andy has taken photos of some small woodcuts of swirls and 90s world market looking signifiers, which were hanging in his therapist’s office. He blew them up, transferred the images into high contrast vinyl decals mounted on plexiglass, and painted a sickly yellow behind them. Rose has hand-made high-end mahogany frames and they are sitting around and a little on top of roughly cut shower liners which display a government health warning in a sensible font. These liners are stapled directly to the wall.

It doesn’t.. reward closer looks.

My eyes go around, getting a little frantic. They can’t settle, and be happy about it. That squiggly swirl? No, can't get it. The one over there? No. I find myself wanting to claw at something, as if I were in a thicket made of the general idea of brambles. Where can I turn. who has done this. What do they want with me?

I came here to see who you were, and you show me these bad communications. Is it because they upset you before? So you want me to look with you.

The labor is sort of displaced, even with the original objects. Nothing here was precious to anyone at any time. Those frames were? Or are they just a wink? They soothe a bit; reassure. The liner’s communication is legally coerced.The swirls are created by whatever consciousness filled Pier One in the 90s.

So these two friends...We are in the space of these two friends.

The initial sense I get is that these two artists are both interested in, and repulsed by, this kind of failed or heavily tortured communication. There is the legally obligated government warning, whose tone is dictated by avoiding liability. And then there are the swirls and random energy markings of the woodcuts—which have more in common with clip art than the ancient cultures they are presumably meant to evoke.

Rose uses her frames to lure you in, play-acting institutional responsibility with that sober natural history museum look, and then disturbing the viewer with the wrongness of the contents.The skill and care, the sheer quality lulls us into a sense of proper management. Surely, these fine frames would only be used for something highly deserving of this time and attention. Like shower liners, roughly cut and stapled to the wall. That's the big shock right there.Because the frames are so considered, this bolt through the skin-like liner is looking pretty deliberately brutal. What an absurd jolt of empathy to have—for a plastic sheet.

In her 2007 book Ugly Feelings, the theorist Sianne Ngai coined the term “stuplimity.” Let me paraphrase her explanation: Stupidity is an unsolvable experience, that can be understood if we invoke the sublime, albeit negatively: stuplimity. The critic Joe Kennedy takes it further and states: “Stupidity has an incalculability which contradicts any redemptive ministrations. It holds its own inanity together with a witnessing incomprehension, but does not mediate the two.”

The makeover Andy undertakes with the swirly woodcuts seems to be an attempt at addressing this impasse. We cannot resolve the problem of stupidity in the work. But there is the option of, as the artist said, informally, “assisting” the work. Making it better. This is an act of empathy and also a bit of disrespect. But the disrespect could be seen as productive rather than plainly mean. This is why I called it a makeover. Makeovers essentially operate in this slightly unstable state, taking energy and permission from a sort of disrespect in the service of a claimed benevolence. (Or maybe the better word is largess). I temporarily erase your own agency in order to make a new you. What is better about these new versions? The emptiness of the signifiers is unchanged, but the delivery is given confidence and polish. The step away from vernacular workshop craftiness gives the emptiness a deliberateness, and a professionalism. It becomes a knowing choice rather than the mistaken self-concept that it is effective in its evocation of an ancient set of meaningful symbols.

The makeover is a success. It looks good. The object has been made acceptable.

But an essential weirdness remains. This reveals another makeover truth—at least part of the goal is to neutralize the weird. Sure, the subject wants to improve, but why? To move easier through the world...because it has not been easy. What makes a subject an uneasy fit? Why do we have the sense that the makeover is incomplete?

They like to say, on makeover shows, that it is about revealing the beauty within. This is a flimsy justification. It is about making others comfortable where once they were not. What if there is no beauty inside the makeover subject? What if they are astoundingly empty? I suspect the makeover effect will be the same. They will still enjoy a new ease in life, and those around them will enjoy how much easier it is to be around them.

LaKaje itself is weird, and a place for other weirdnesses to be.

The space takes you off guard by taking you seriously. How can you tell? Because you don’t get a sense that they are seeking a pre-determined audience. There is no assumption about how the experience should go or who exactly you are. So, that must mean they are open to different kinds of communication than I, as an audience-person, am accustomed to being expected to provide. It’s almost disorienting to be suddenly confronted with a space that is listening to you with a genuine curiosity.

Why is the question of a intelligible audience seemingly given so much weight in institutions? Why is it expected to be answerable? Isn’t it obvious that defining an audience forces the audience to define itself in relation to the definition, and back and forth down a spiral of inanity? Isn’t it awfully close to how brands seek out consumers? A marketing question? Even if you think you're benevolent, you're trying to smooth out the weird. If the question has been asked of them - who is your audience? It seems they’ve decided the answers are along the lines of:

We’ll never know for sure. It varies.

You, for now.

Sarah Lassise, 2019