Werpos

Voluminous Arts, Gavilán Rayna Russom, October 5th, 2022

To begin Voluminous Arts’ 6-month residency at Kaje Projects, label founder Gavilán Rayna Russom shares some of her preliminary research on Gowanus, the neighborhood in Brooklyn where Kaje is located. Through the lens of that research, she explores connections between the neighborhood’s industrialization and her approach to designing this “research residency”.

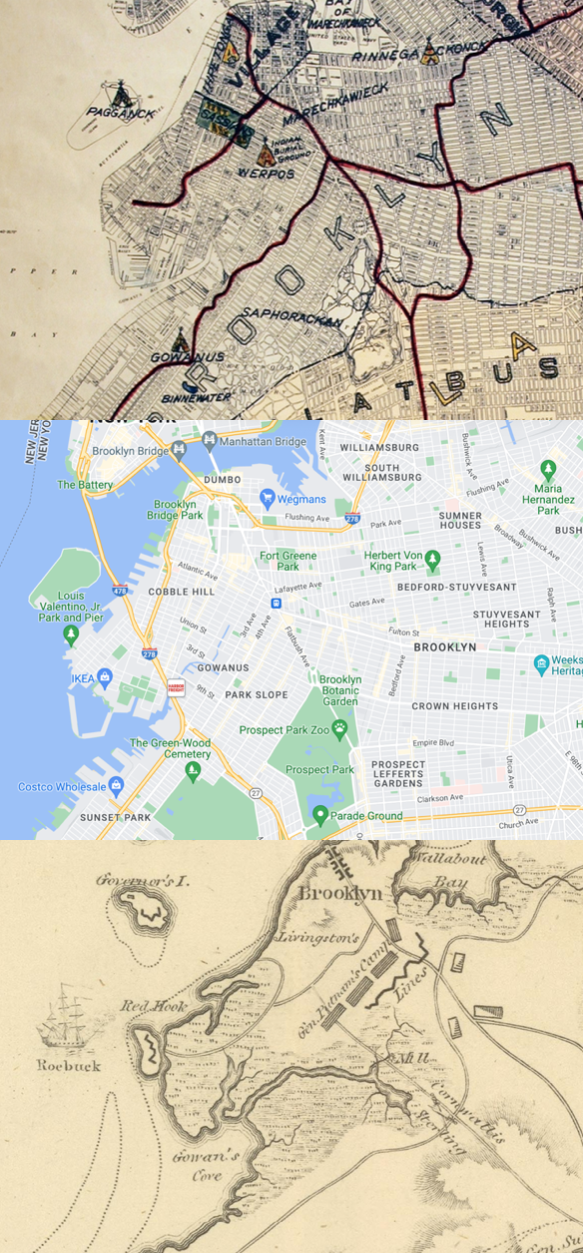

WERPOS is a site within the ancestral and living homeland of the Canarsee people. It is currently occupied by a contested settler colonial entity called Gowanus, Brooklyn. The word Werpos describes a landscape that includes an area that is elevated above nearby waterways, which it overlooks. Until 1626 there was a village of dwellings present on the site and, according to a 1946 map, a burial site. The lands around the place called Werpos in the Canarsee language - a dialect of Munsee Lenape - are also an ancestral and living homeland to several Algonquin peoples. The relationships between the overlapping lifeways of these diverse peoples were held in balance for thousands of years (before the arrival of Dutch settler colonists) by treaties and protocols that facilitated rich and sophisticated ways of being with each other on shared land despite differing traditions and beliefs. These treaties and protocols included understandings about how to relate to the land which areas of it were suitable for dwellings, which were suitable for hunting and gathering (and at which times of the year), which were suitable for burial sites, which were suitable for planting crops and which should be left as undisturbed as possible. These protocols were, and still are, often misunderstood by settler colonists. Even well-meaning scholars and activists will sometimes use the archeological evidence of dwellings as a way to identify Native homelands as separate from “unused” land. It is important to understand that whether or not a Native dwelling ever existed on a given piece of land all land is Indigenous land.

As a white woman of settler colonial ancestry, I do not know the Indigenous protocols which held Werpos and its surrounding lands in balance, nor can I claim to understand them. As part of the process of preparing to be in residency at Kaje on the ancestral and living Native homelands around Werpos, I have done my best to begin to research them and let that research guide my presence, and the presence of my label Voluminous Arts on the Indigenous lands where the residency is taking place.

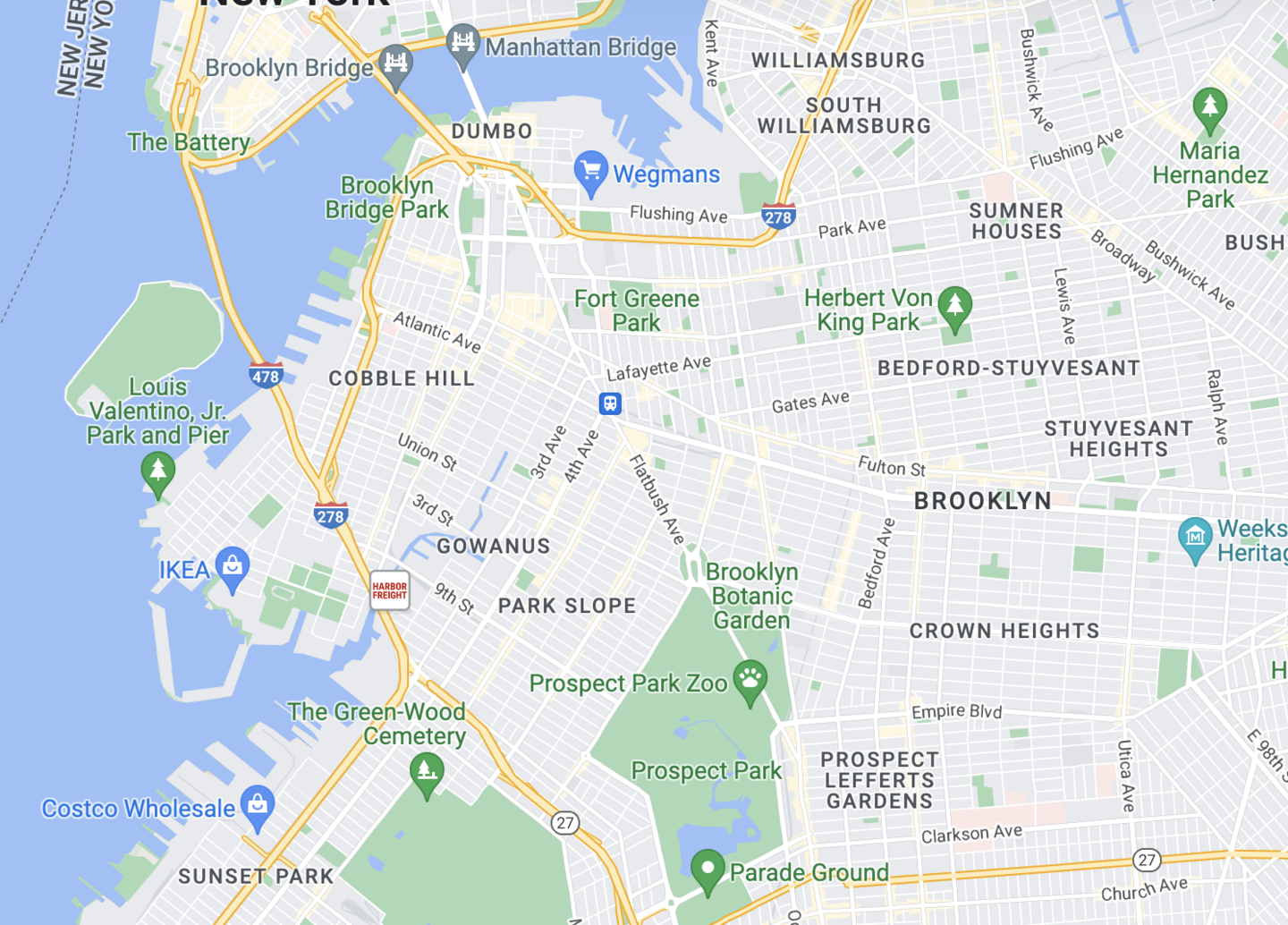

Central to this research is the Gowanus Canal, perhaps the most prominent feature of the neighborhood. The present-day Gowanus canal was constructed on an existing waterway. While I know that it was named the Gowanus Creek by settlers, I have not yet been able to learn Indigenous names for it. The origins of the term Gowanus are unclear but several sources suggest it refers to Gouwane, a Canarsee chief with whom early Dutch settler colonists made unclear and predatory agreements, keeping his name as a memorialization.

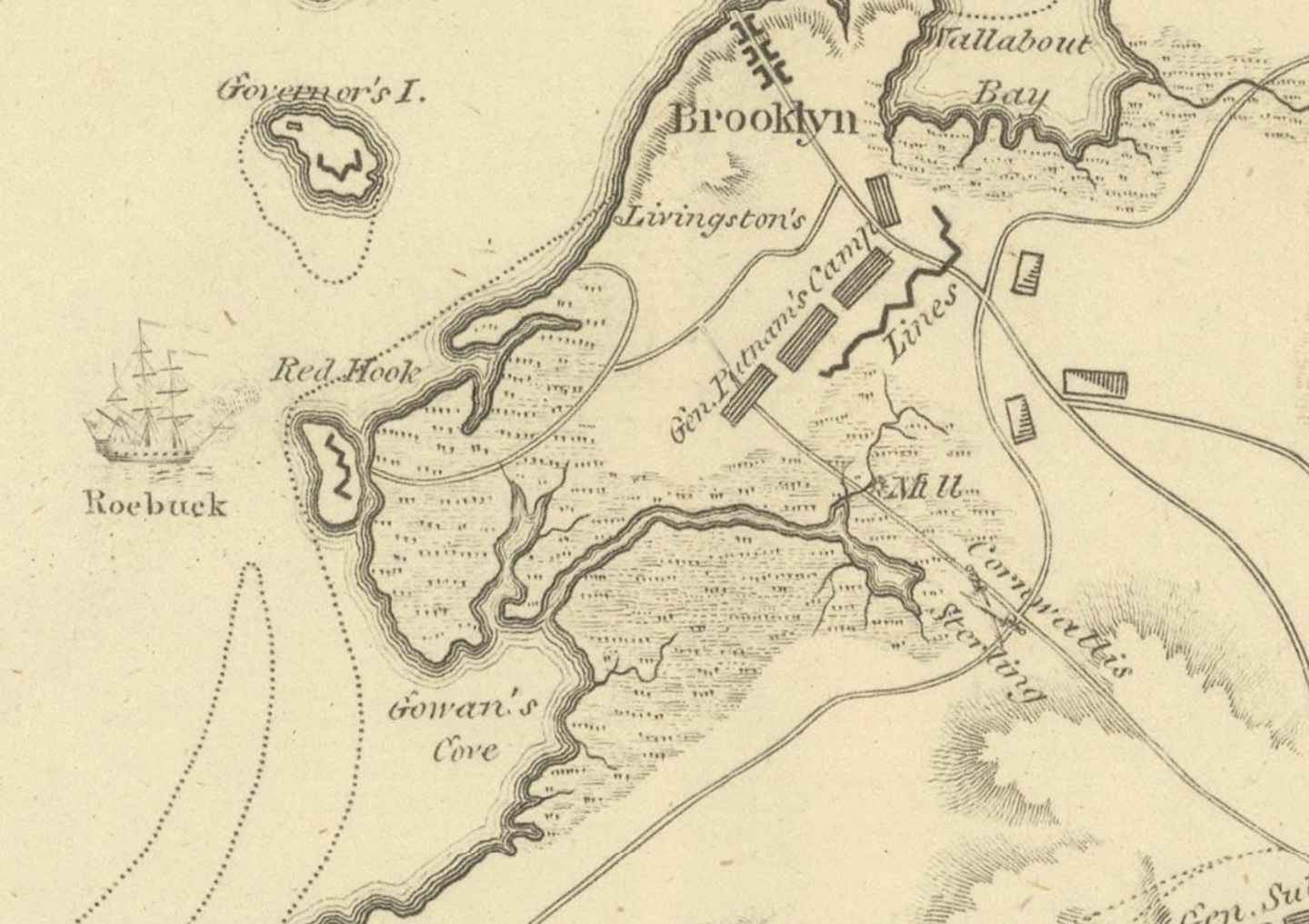

The creek which was adapted to create the canal was part of an astoundingly rich marshland ecosystem. Early Dutch accounts marvel at the natural abundance of the area. Underground springs fed the creek, causing it to develop distinct tidal qualities that encouraged a slow and specific type of refreshing of its waters, as well as those at the mouth of the nearby bay and within the marshland that extended outwards from the creek’s banks. Marshland is not vague, undifferentiated land as is suggested by many ways that it is framed in the English language through settler colonial frameworks. It is highly specific, despite the fact that it exceeds categorization in rigid terms that emerge from those frameworks’ inability to understand its value. The marshland around Werpos was neither land nor water but a liminal space with qualities of both, as well as qualities of its own. This liminality - held and protected from human disturbance by Indigenous protocols that evolved over thousands of years - is what was responsible for the natural richness of the area and its ability to sustainably nourish human, animal and plant lifeways.

Dutch settler colonists initially built upon this ancestral and Indigenous knowledge to extract the resources of the area for trade. The area called Gowanus by these settler colonists was the first colonial settlement in what would become New York. It is the place where the story of New York’s commercial development as a settler colonial site of resource extraction and trade begins. Indigenous protocols were an obstacle to the levels of resource extraction required by early capitalism to generate and stockpile wealth and were abandoned in favor of industrial development. This abandonment of Indigenous protocols went hand in hand with persistent and genocidal attempts to eradicate the presence of those individuals who held and practiced them.

A component of the area’s industrial development was the transformation of the Gowanus Creek into the Gowanus Canal. This required creating a strict and regimented binary between land and water and the eradication of the more liminal and spectral marshland. Enforcement of this binary on the liminal, spectral and non-binary marshland meant filling in areas that, from an industrial capitalist viewpoint, tended towards definition as “land” but still contained “water” and scooping out areas that tended towards definition as “water” but still contained “land”. The complex identity of the marshland ecosystem, which not only resisted binary categorization as “land” or “water” but drew its richness from that resistance, was reduced and flattened, using violent means, into a segregated and strict binary of: fluid canal = useful for transporting goods by boat to the harbor and solid banks = useful for loading goods onto boats. Adapting the land and waterways to advance the agendas of capitalism and settler colonialism required the artificial creation of a binary through violence.

The creation of this binary had disastrous results for the ecosystem. Filling in the areas where springs had previously fed the creek meant the canal quickly became stagnant. Dumping of building materials into the marshy wetlands to make them into solid land meant the rich lifeways of plants and animals for whom they were a homeland were terminated. Quickly and increasingly the canal became a dangerous site of extreme pollution and a public health hazard. Recent initiatives to clean up the canal have tended to be in service of gentrification agendas geared towards creating valuable “waterfront real estate” in Brooklyn. They are firmly inscribed within the initial problem of settler colonialism and thus cannot possibly present workable solutions to the environmental problems that arise from it.

There are connections between the need for early Dutch settler colonists to violently transform the marshlands near Werpos into the fixed binary of the Gowanus Canal to advance agendas of resource extraction and the ways in which currently dominant political and social frameworks violently reduce and regiment expansive, complex and highly specific embodied experiences of gender and sexuality into rigid and limited cis and hetero-normative binary categories. These tendencies of settler colonial frameworks to reduce and regiment are also connected to the need within creative industries to flatten experimental and interdisciplinary forms and practices into genres and disciplines to more effectively market them.

When Kate Levant and Jacques Vidal reached out to me about the research residency at Kaje, they described it as a “think tank”, not particularly focused on producing clear public facing artworks, but more of a time-in-space to explore topics and themes. It was a welcome invitation, specifically because of how much writing and speaking I’ve done about the settler colonial dimensions of reliance within creative industries on fixed genre categories and artistic disciplines as requirements for success and support. In addition to linking this need to regiment expansive creativity to larger frameworks present within Eurocentrism and settler colonialism, I have also consistently identified it as specifically detrimental to the work and lives of trans, non-binary and gender variant people. In the first weeks of the residency, I met with Yvonne Lebien (one of the artists that Voluminous Arts works with) in the space and attempted to explain to her how I was approaching the residency saying, “The hope is that this physical space can be a liminal space between something you have in your head and a potential ‘finished’ public facing version of that idea.”

Having spent the lead-up to the start of the residency on September 1st researching the canal and the Indigenous lifeways of the area, something clicked as those words left my mouth. There is a relationship between this gift of a research residency as a liminal space for exploring experimental creativity, the richness of queer, non-binary, trans and gender variant experience and the rich spectral qualities of the marshlands near Werpos. My hope is that this six-month period will provide opportunities to restore some of the inner marshlands of individuals affiliated with the label in the absence of the pressure to create any kind of “product.” These inner marshlands, like the natural landscapes they echo are also not vague, unclear or undeveloped. They are simply specific in ways that exceed categorization, definition and legibility within a system of categorization based on capitalist market values and the settler colonial frameworks that uphold them. Much of this “restoration” relies, like the marshland ecosystem, on interconnectedness.

To be clear, I do not claim to be employing, nor am I attempting to employ, Indigenous protocols myself during this time. I am, however affirming that they are more suited than Eurocentrist and settler colonial frameworks can ever be to creating sustainable lifeways that support expansive experiences of gender and sexuality as well as creative expressions that exceed fixed market categories. The evidence of this is the tens of thousands of years during which Indigenous protocols supported an incredibly rich ecosystem within the water and land ways around Werpos and the devastation of that ecosystem in service of the short-sighted agendas of capitalism over the mere hundred years since the creation of the now stagnant and polluted Gowanus Canal. This is one of the many reasons why land back is an exponentially more worthy focus of energy than ecological initiatives that continue settler colonial agendas in service of developing the neighborhood as a site of valuable “waterfront real estate.” In recognition of this, at the center of this residency project is an intention and a commitment that the time that Voluminous Arts spends at Kaje will sit within the larger process of healing and decolonization within the Indigenous homeland that surrounds Werpos.

If you are an artist who identifies as trans, non-binary, two spirit or otherwise gender non-conforming and would like to submit a proposal for an activity as part of the Voluminous Arts research residency at Kaje Projects, please email contact@voluminousarts.com for a proposal submission form. I cannot guarantee that we will be able to accommodate all requests but I will do my best, with preference given to QTBIPOC folks. If you are an Indigenous person or part of an Indigenous led collective or organization, I would be overjoyed to speak with you about practical steps towards land back in the ancestral homelands around Werpos. Feel free to contact me directly at rayna@voluminousarts.com.

Some of the activities happening during the residency will be open to the public, many will not. Please check @voluminousarts on Instagram or subscribe to our mailing list at www.voluminousarts.com for updates.

Sources:

Ancken, Victoria L Von. “The Gowanus Canal: Delving into the Murky and Mysterious Waters of Brooklyn’s Toxic Canal,” 2016.

Estes, Nick. Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. London: Verso, 2019.

Kovach, Margaret. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

“Map of New-York Bay and Harbor and The Environs.” Accessed September 19, 2022.

Otero, Solimar. “Yemaya y Ochún: Queering the Vernacular Logics of the Waters in Afro-Cuban Religion” in Yemoja : Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas. Eds Otero, Solimar, and Toyin Falola. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2013.

Rubertone, Patricia E. Native Providence: Memory, Community, and Survivance in the Northeast. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020.